The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimate that nearly 1.5 million people die each year from viral hepatitis. To give you some context, that’s the entire population of Trinidad and Tobago dying each year, and is equivalent to 4000 deaths each and every day. Many of these infections are preventable but most people do not know how.

Tuesday July 28th 2015 marked World Hepatitis Day, created by the World Hepatitis Alliance with the support of the WHO and over 200 international organisations. The vision: Seeking a world without viral hepatitis.

One aim of World Hepatitis Day is to raise awareness of viral hepatitis: how viral hepatitis is transmitted, the consequences of infection, and what you can do to reduce the risk of infection.

Viral hepatitis – the facts

Hepatitis can be a serious and deadly disease, which can affect anybody worldwide. Hepatitis refers to inflammation of your liver, the second largest organ in the body. Your liver has hundreds of functions; it is responsible for removing toxins and waste products from your body, fighting infections and controlling cholesterol levels. Hepatitis can interfere with these functions, leading to significant morbidity and mortality.

“Chronic hepatitis often doesn’t cause any symptoms until liver disease is advanced, hence being known as ‘the silent killer’.”

Worldwide, hepatitis is most commonly caused by viruses. There are five main hepatitis viruses: A, B, C, D and E (HAV, HBV, HCV, HDV, HEV). HAV and HEV are mainly spread by ingesting food and water contaminated by faeces, whilst HBV, HCV and HDV are blood-borne infections.

Initial symptoms can be non-specific, similar to the ‘flu; some people develop jaundice, itchy skin or a swollen, tender liver. In the cases of HAV and HEV, this illness is mostly short-lived (meaning less than six months). 90% of adults are also able to clear HBV infection, however 90% of children will become chronically infected after exposure. Only 15% of people are able to clear HCV without treatment. HDV is only able to infect people who have HBV but it can speed up liver damage.

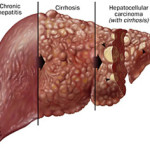

If the body is not able to clear the virus, chronic hepatitis results which leads to progressive liver scarring, liver cancer, failure of the liver to function properly and death. It is rare to clear chronic hepatitis without treatment. Chronic hepatitis often doesn’t cause any symptoms until liver disease is advanced, hence being known as ‘the silent killer’.

HBV and HCV – the big two

It is estimated that 400 million people are infected with HBV and HCV worldwide, and over one million die every year from complications associated with their infections. Most of these occur across Sub-Saharan Africa and Asia; <1% of people are infected across Europe.

In endemic areas, HBV is commonly spread from mother to child at birth. It can also be spread by the sharing of contaminated needles, syringes and injecting paraphernalia by people who inject drugs (PWID), or by unsafe medical injections and transfusions. Sexual transmission may also occur.

HCV is mainly spread by percutaneous exposure through the use of contaminated injection equipment. Transmission can also occur when sharing notes and straws for intranasal drug use. In contrast to HBV, spread from mother to child and transmission through sex is rare.

“Although challenging, we have in our hands the tools to rid the world of viral hepatitis…”

Critically, each of the 400 million infected worldwide may pass the virus on to other susceptible people, particularly if they are unaware of their infection. Our fight against these viruses therefore relies upon accurate diagnosis and treatment of those who are infected combined with prevention of new infections.

We can stop the spread of viral hepatitis

We have in our hands the ability to curb the spread of HBV and HCV.

- Treatment as prevention

Chronic HBV can be treated with drugs that are able to stop the virus growing and can reduce symptoms. These treatments also reduce the risk of transmission to others but rarely cure the infection meaning that treatment is often life-long.

In contrast, treatment of HCV is curative. There has been a recent breakthrough in the development of effective antivirals that can eliminate the infection. However, these drugs are often prohibitively expensive, even in high-income countries and administration of them requires accurate diagnosis of disease, limiting their impact at population level.

- Vaccination

The mainstay of prevention of HBV is vaccination. Since 1982, HBV has been a vaccine preventable disease, like measles and mumps. The WHO recommends that all infants receive the HBV vaccine as soon as possible after birth, preferably on the first day of life, with more doses following soon after.

The majority of United Nations Member States vaccinate infants against HBV. Vaccinations are also recommended for people in high-risk groups including household and sexual contacts of people with HBV infection, PWID and healthcare workers. HBV vaccination also limits the spread of HDV.

Unfortunately, not every at-risk individual or child receives all doses of the vaccine and the vaccine is ineffective in a small percent of recipients. As a consequence, cases of HBV continue to occur. Additionally, there is currently no vaccine available to prevent HCV infection and we must look to alternative strategies.

- Health promotion: Safe injection strategies, blood safety strategies and sexual health

A large fraction of new cases each year are caused by unsafe injections, through re-use of unsterilised needles and syringes. About 16 billion injections are given each year in non-developed countries, many of which are considered unsafe (and often unnecessary). Unsafe injections may be caused by a number of reasons, including lack of awareness about the risks of unsterilized equipment or a lack of resources. This can be tackled through educational campaigns and an increase in medical equipment supplies.

Ensuring quality controlled screening of all donated blood and blood components can also prevent spread of disease. Finally, advocating safer sex practices, including minimising the number of partners and using barrier contraception, should be an integral part of any risk reduction strategy.

World Hepatitis Day

Although challenging, we have in our hands the tools to rid the world of viral hepatitis, if everyone plays their part: know the risks, demand safe injections, be vaccinated, get tested, seek treatment.

To this end, the first ever World Hepatitis Summit will be held in Glasgow, Scotland, UK in September 2015 to aid the creation and implementation of action plans through sharing of best practice. You can support World Hepatitis Day and the summit through the #4000voices campaign online.

************************

By Connor Bamford (@cggbamford) and Naomi Bulteel (@nimbulteel)

The MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research undertakes a broad research program into HCV biologyranging from epidemiological and clinical to molecular and cell biological studies. This research is led by the principal investigators: Dr Carol Leitch (HCV evolution); Dr John McLauchlan, associate director of the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research (HCV cell biology and immune responses, as well as being a leader of the ‘HCV Research UK’ ‘Biobank’); Dr Arvind Patel (HCV entry and vaccine development) and Dr Emma Thomson (HCV evolution and treatment in the clinic).