A group of small curious caterpillar-like predators hide among forest litter and soil of rainforests and other moist habitats: the onychophorans. Despite few onychophorans species are known worldwide, their anatomical, reproductive and ecological traits make them a unique and independent group of animals. Would you like to know more about them? Keep reading.

Is it as worm? Is it a caterpillar? NO! It is an onychophoran

Onychophorans or velvet worms are a phylum of small invertebrates that range from 5mm and 15cm, with soft, long and almost non-modified bodies and small conical unjointed legs like those of caterpillars.

The scientific name of the group, Onychophora, is formed by the Ancient Greek terms onykhos, “claws” and phorós, “to carry“, since on each foot they have a pair of retractable, hardened (sclerotised) chitin claws.

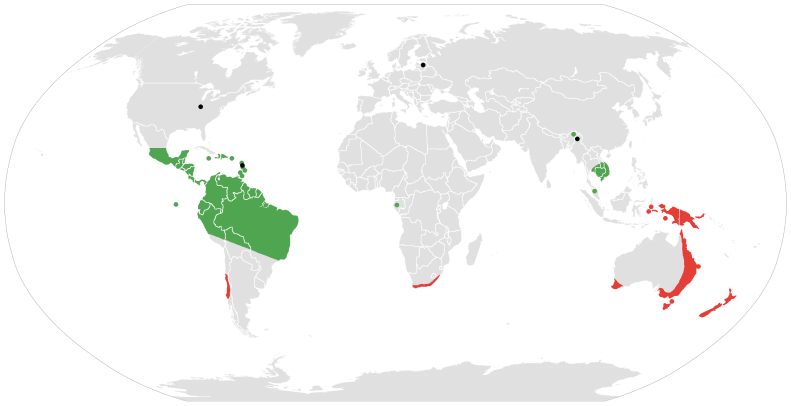

Currently, about 200 species of onychophorans are known worldwide, all of them terrestrial, distributed exclusively in the Southern Hemisphere. They are classified within two families with a mutually exclusive distribution: Peripatidae, with a circumtropical distribution (mainly found in Mexico, Central America, north of South America and Southeastern Asia), and Peripatopsidae, with a circumaustral distribution (mainly Australasia, South Africa and Chile).

Some fossil records that date from the early Cambrian suggest that ancient onychophorans probably appeared barely after the Cambrian Explosion and that they eventually moved from water to land.

Who do onychophorans look like?

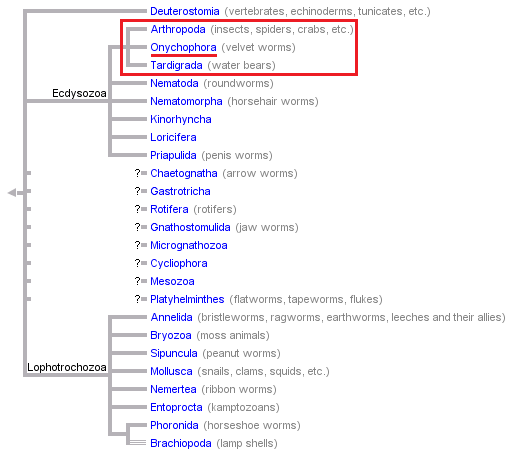

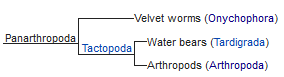

To date, the most widely accepted idea from both an anatomical and a morphological point of view is that they constitute an independent phylum within Ecdisozoa, i. e., organisms that undergo consecutive molts or ecdysis to change their cuticle, closely related to tardigrades or water bears and arthropods (insects, arachnids and their related groups, myriapods, crustaceans and the extinct trilobites).

Onychophorans, arthropods and tardigrades all together constitute the Panarthropoda group, a monophyletic taxon, i. e., that groups all the descendants of a common ancestor, which validity has been proved by most of studies.

So, despite resembling worms (annelids), slugs (gastropod mollusks) or caterpillars (lepidopteran larvae), onychophorans do not belong to any of these groups.

Anatomy

Onychophorans have long bodies covered with a thin, flexible chitinous cuticle with pseudo-segmented markings or weak ringed marks. Its cuticle is also covered in tubercles or papillae with sensilla, i. e., small and thin hairs, which give these animals a velvety appearance that gives rise to their common name.

Their bodies are internally divided into true segments each with a pair of soft, conical, unjointed legs or lobopods, in contrast to those of arthropods. Their movement is from front to back, in a wave, and each pair of legs move in the same direction, so that their way of walking is slow and gradual, making them almost invisible to prey.

The head houses a pair of mandibles, a pair of tiny eyes with chitinous lenses and a developed retinal layer, and a pair of fleshy sensorial appendices resembling antennae of arthropods, but with which they do not share an evolutionary or embryonic origin. They also have a pair of oral papillae near the mouth, each connected to a slime gland that produces and whitish sticky substance or slime they use to hunt or as a defense. These glands occupy almost the entire length of their bodies.

Ecology and behaviour

Most of species live primarily in moist, dark microhabitats, such as forest litter and soil, of rainforests or other types of very rainy forests. They are solitary, nocturnal and photonegative, i. e., they hide from light. A very few species are cave dwellings or live in drier woodlands.

All onychophorans are active predators. They hunt pray by shooting an adhesive substance or slime through their oral papillae to immobilize them. They can shoot this substance up to 30 cm:

The slime is 90% water, while its dry residue consists mainly of proteins, sugars, lipids and the surfactant nonylphenol. Onychophorans are the only known organisms able to synthetize the latter substance, which has been widely produced and used by humans for manufacturing, for example, lubricating oils and detergents.

Reproduction

Mating and fertilization

All onychophorans, except the parthenogenetic species Epiperipatus imthurni, reproduce sexually. Females and males show a moderate degree of sexual dimorphism, with females being somewhat larger than males and, in species with a variable number of legs, females have more legs than males.

Fertilization is always internal, even though the way females receive the sperm from males is quite variable. In most onychophorans, males transfer a spermatophore, i. e., a package of sperma, directly to the female’s genital opening. Males of a few species within Paraperipatus genus use a true penis to complete this transference.

However, the strangest case is that of two species within Peripatopsis genus. Males place very small spermatophores on the back or sides of the female; then, amoebocytes from the female’s blood collect on the inside of the deposition side to secrete enzymes that decompose both the spermatophore’s casing and the body wall of the female on which it rests. This releases the sperm, which travels through the female’s blood or haemocoel to reach the ovaries, where fertilization takes place.

Types of reproduction

Onychophorans may be oviparous, ovoviviparous or viviparous.

The most common are the ovoviviparous forms, i.e., very well-developed eggs provided with yolk are retained inside the female’s body and they hatch barely before she gives birth. These forms are exclusively found within the Peripatopsidae family.

Oviparous forms, which are less common, have been observed in organisms inhabiting habitats with non-stable food sources and instable environmental conditions where the egg shell and other eggs structures would act as a protective barrier. As it happens with the ovoviviparous forms, the oviparous are exclusively found within the Peripatopsidae family.

On the contrary, viviparous forms are very well-represented in tropical regions with stable environments and food sources both in Peripatopsidae and Peripatidae (the latter with a circumtropical distribution). Females produce very small eggs that are retained inside her uterus and nourished directly by maternal fluids or specialized tissues from the mother’s body (placenta). Several weeks or months later, females give birth to well-developed offspring.

. . .

If you found this entry interesting, feel free to leave your comments!

Main photo by Melvyn Yeo (c)