Abstract

In recent years, introduced synanthropic species of the order Zygentoma (especially Ctenolepisma longicaudatum and C. calvum) have begun to spread in Central Europe. The two above-mentioned non-native species of silverfish have also recently been confirmed in Slovakia. This paper aims to comment on the occurrence of the two non-native species in Slovakia, to compile an identification key for all (i.e. also native) Slovak silverfish species and establish local species names.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Zygentoma is an order of insects currently included in the class Insecta, consisting of about 650 species and six families (Robla et al. 2023), encompassing silverfish or fishmoths and firebrats. Silverfish (Lepismatidae) are small arthropods feeding on cellulose-based material. The last common ancestor with the remaining Dicondylia dates back more than 400 million years (Misof et al. 2014).

Their last common ancestor dates over 400 million years ago (Misof et al. 2014). The order includes the so-called silverfish or fishmoths and the firebrats belonging to the family Lepismatidae, which are small arthropods feeding on cellulose-based materials (e.g. Pothula et al. 2019).

Silverfish are indoor pests in homes, offices, museums, and galleries, causing harm to objects such as paper, books, photographs, and wallpaper (Trematerra and Pinniger 2018).

In particular, the grey silverfish (Ctenolepisma longicaudatum) is receiving increasing attention as a pest of cultural heritage in collections worldwide. In museums, archives and libraries, C. longicaudatum is a recognised pest that has damaged many objects in recent years. However, according to some authors (e.g. Querner and Sterflinger 2021, 2022), it requires high humidity (> 70% RH), so this species can only damage paper-based materials in humid areas. Although such risks are known for Lepisma saccharinum, the species seldom causes damage to objects. In homes, most silverfish (Lepismatidae) are not true pests but nuisance animals.

At the moment, eleven species are regularly recorded in Central Europe. Only six of them are recorded in Slovakia: the common silverfish Lepisma saccharinum Linnaeus, 1758; the firebrat Thermobia domestica Packard, 1873; Atelura formicaria Heyden, 1805 (species living in ant nests); and three recently introduced species: the invasive grey or long-tailed silverfish Ctenolepisma longicaudatum Escherich, 1905, the four-lined silverfish Ctenolepisma lineatum (Fabricius, 1775), and C. calvum (Ritter 1910). The exhaustive distribution of L. saccharinum in Europe was reviewed by Claus et al. (2022) with emphasis on its populations in redwood ant nests (Formica rufa group), although it is more common in buildings. Atelura formicaria is mainly restricted to habitats outside buildings (Christian 1994), while all other species are mostly related to human activity and found in interiors. Ctenolepisma lineatum is also found outside buildings in some European countries, a facultative synanthropic species. Further, five species were not recorded in Slovakia until now: Coletinia maggi (Grassi, 1887) recorded from Austria (Christian 1993) and Hungary (Paclt and Christian 1996), Nicoletia phytophila Gervais, 1844 recorded from Germany (Weidner 1983) and Switzerland (Gilgado et al. 2021), and three species recorded only from Germany (see Weidner 1983): Stylifera impudica Escherich, 1905, Gastrotheus ceylonicus(Paclt, 1974) and Ctenolepisma rothschildi Silvestri, 1907. Still, these five species are not known as common insects in homes and buildings.

The spread of non-native Lepismatidae in Europe

Recent years have witnessed an increase in synanthropic Lepismatidae species in Central Europe, with new species being introduced and spreading across the continent (e.g. Christian 1993; Kulma et al. 2021):

Ctenolepisma longicaudatum, an invasive silverfish species, has been passively introduced to most European territories (for details on its spread up to 2021, see Kulma et al. 2021).

Ctenolepisma calvum – its origin and native range are unresolved. The first reports of C. calvum came from Ceylon (Ritter 1910; Crusz 1957), followed by Guyana and Cuba, where it was reported as a common house lepismatid by Wygodzinsky (1972). The first European reports came from Chemnitz, Germany (Landsberger and Querner 2018) and Norway (Hage et al. 2020), although authors use no appropriate microscopic characters to identify this species conclusively. For details on the species spread up to 2021, see Kulma et al. (2022).

Ctenolepisma lineatum is native to the warmer regions of Central Europe and the North Mediterranean basin (Molero-Baltanás et al. 2012). However, the species reached other parts of the world through trade and transport (for details on its spread in Europe up to 2020, see Hage et al. (2020).

History of research on Zygentoma in Slovakia

The first works on Zygentoma from the territory of today’s Slovakia appear only at the end of the 19th century. In this period, zoologists paid little attention to the faunistic research of silverfish in Slovakia. The earliest faunistic data from the territory of present-day Slovakia can be found in the works of the Austro-Hungarian zoologist Tömösváry (1884). At the end of the 19th century, Uzel (1891, 1897, 1898) contributed to the knowledge of the embryonic and postembryonic development of Zygentoma. Petricskó (1892) reports the occurrence of C. lineatum from the vicinity of Banská Štiavnica. Vellay (1899) was the last to publish his faunistic findings on Zygentoma in the iconic work Fauna Regni Hungariae at the end of the 19th century.

Faunistic research after World War II

Apart from a record of Kratochvíl (1945), who reported C. lineatum from Slovakia, no one systematically studied silverfish until the 1950s. Paclt (1951) reports a record of A. formicaria from Bratislava. Paclt (1956) reports a single locality and a single specimen of C. lineatum from southwestern Slovakia (regional name Žitný ostrov). Paclt (1959) published a summary work on Slovak Zygentoma, listing L. saccharinum, C. lineatum, and A. formicaria. Later, he also published two important monographical works on Zygentoma: the first one on the family Nicoletiidae (Paclt 1963) and the second one on the remaining families Lepidotrichidae, Maindroniidae and Lepismatidae (Paclt 1967). Ctenolepisma lineatum was also reported in Ivanka pri Dunaji in 1966 (Paclt 1979), where it was recorded again in 2021–2023 (V. Hemala, unpublished data). In 1975, a faunistic survey of greenhouses in Bratislava was carried out by Krumpál et al. (1997). Their paper only mentions the species C. lineatum from the palm greenhouse of the Botanical Garden in Bratislava. Some records of A. formicaria were given in works focused primarily on other myrmecophilic arthropods, e.g. in Pekár (2004) as the observation during the study of ant-eating Zodariidae spiders or in Majzlan’s (2009) study of the occurrence of the ant cricket Myrmecophilus acervorum (Panzer, 1799) in Slovakia. Majzlan’s (2009) records of A. formicaria were also cited in the later actualisation of the Slovak occurrence of M. acervorum in Franc et al. (2015). Rusek (1977) provided the first checklist of Czechoslovak Zygentoma, where Thermobia domestica (Packard, 1837) was also listed for all parts of former Czechoslovakia, including Slovakia. However, these records were not found in any work published before 1977. It is possible that T. domestica was only collected and preserved but not published due to considering it a common species. This work aims to comment on the records of two new species for Slovakia, compile an identification key and establish local species names.

Materials and methods

Morphological study

Preserved and living specimens were studied at different magnifications without any treatment with the help of a ZEISS Stemi 305 stereo microscope (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) and Olympus BH2-BHT research upright microscope (Olympus Corporation, Shinjuku, Tokyo, Japan). Photographs were taken using a custom-made microscope based on ZEISS AMPLIVAL research upright microscope (VEB Carl Zeiss JENA, Jena, Deutsche Demokratische Republik) body equipped with Mitutoyo M Plan APO objectives (Mitutoyo Corporation, Sakado, Japan) and Canon EOS80D digital camera (Canon Inc. Operations, Ohta-ku, Tokyo, Japan) and by Keyence VHX-7000 N equipped with VH-ZST objectives (Keyence Corporation, Osaka, Japan). Photographs were focus-stacked using Helicon Focus Software (HeliconSoft Helicon Soft Ltd., Kharkiv, Ukraine). Individuals of both species were identified using available identification keys (Theron 1963; Wygodzinsky 1972; Molero-Baltanás et al. 2000, 2015; Aak et al. 2019; Kulma et al. 2022).

Results

Considering the records of new species, six species of silverfish currently occur in Slovakia, three of which are native to the Slovak fauna (Table 1).

Ctenolepisma longicaudatum Escherich, 1905

Ctenolepisma longicaudatum (Figs. 1 and 2) was recorded in the washrooms of the manufacturing building in Dolný Kubín-Mokraď, Slovakia, on November 14, 2017 (iNat ID: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/8804678; accessed on 05 January 2023), and consequently at the same location and different places of the building on December 13, 2018 (iNat ID: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/19155466; accessed on 05 January 2023); October 19, 2021 (iNat ID: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/98730948; accessed on 05 January 2023); September 7, 2022 (iNat ID: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/145497900; accessed on 05 January 2023); December 26, 2022 (iNat ID: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/145182284; accessed on 05 January 2023); January 05, 2023 (iNat ID: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/145891809; accessed on 05 January 2023); these represent the first documented records for Slovakia. The identification of the first specimen, shown in Fig. 1, was suggested by Nikola Szucsich on iNaturalist (n.d.) (https://www.inaturalist.org) and consequently confirmed by the authors based on morphological characters presented in Figs. 2, 3, and 4.

Ctenolepisma longicaudatum: a head dorsal view where the cephalic tufts of macrosetae (red arrow) and the setal collar of the pronotum (black arrow) are visible (upper left), b head ventral view showing labial palps (visible at the bottom of the photo), c dorsal view of abdomen showing lateral bristle combs – infralateral (blue arrows), lateral (green arrows), sublateral (white arrows), note all three types of bristle combs on urotergites V and VI (middle left), styli of the abdominal sternites VIII (yellow arrow) and IX (orange arrow) are also visible, d ventral side of the posterior part of the female abdomen showing bases of cerci, median filament and two pairs of abdominal styli of the abdominal sternites VIII (yellow arrow) and IX (orange arrow) (middle right), e detail of a compound eye (lower left), f micro photos of scales (lower right), December 26, 2022, Dolný Kubín-Mokraď, Slovakia, Photo by F. Bednár

Ctenolepisma calvum (Ritter, 1910)

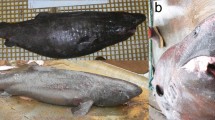

On June 11, 2021, C. calvum was spotted and caught in a family house bathroom in Švošov, Ružomberok District, Slovakia (iNat ID: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/106751642; accessed on 05 January 2023) (Fig. 5). Since then, it has been spotted many times, for instance, on March 6, 2022 (iNat ID: https://www.inaturalist.org/observations/108247596; accessed on 05 January 2023). This record represents the first documented record for Slovakia. The first specimen was identified, and Nikola Szucsich confirmed consequent findings on iNaturalist (n.d.) (https://www.inaturalist.org). Figures 6 and 7 present detailed images of specimens caught at the same site, and Fig. 8 illustrates a comparison of scales of both C. longicaudatum and C. calvum.

The identification of the first specimen, shown in Fig. 5, was suggested by Nikola Szucsich on iNaturalist (n.d.) (https://www.inaturalist.org) and consequently confirmed by the authors based on morphological characters presented in Figs. 6 and 7.

Ctenolepisma calvum: a dorsal head view where the cephalic tufts of macrosetae (red arrow) and the setal collar of the pronotum (black arrow) are visible (upper left), b ventral head view where the cephalic tufts of macrosetae (red arrow) are visible (upper right), c dorsal view of abdomen showing lateral bristle combs – infralateral (blue arrows), lateral (green arrows), sublateral (white arrows), note only two pairs of macrosetae on urotergite VI (blue and white arrow), one of the diagnostic characters, which separates C. calvum from C. longicaudatum, styli of the abdominal sternite IX (yellow arrow) are also visible (middle left), d ventral side of the posterior part of the female abdomen showing one pair of abdominal styli (yellow arrow), e detailed ventral view showing lateral bristle combs, f micro photo of scales (lower right), December 26, 2022, Dolný Kubín-Mokraď, Slovakia, Photo by F. Bednár

Key to the species of Zygentoma with confirmed occurrence in Slovakia

This key is partly adapted from the key provided by Molero-Baltanás et al. (2000) with the addition of C. calvum according to the morphological diagnosis provided by Kulma et al. (2022). The morphological terminology is reviewed according to the morphological terms broadly used in Molero-Baltanás et al. (2012) and the most recent works on Zygentoma taxonomy and morphology (e.g. Molero et al. 2018; Molero-Baltanás et al. 2022; Smith 2017; Smith and Mitchell 2019) (Fig. 9). Species with unconfirmed but possible occurrences in Slovakia are mentioned in square brackets. Zygentoma can be confused with members of Microcoryphia by the lay public. Still, the main difference is the absence of any jumping mechanism in Zygentoma (e.g. Mendes 2002) and other characters: (a) eyes large, strongly conspicuous and touching each other in Microcoryphia and smaller, inconspicuous or absent in Zygentoma; (b) absence of ocelli in Zygentoma (except the family Tricholepidiidae); (c) maxillary palpus consists of 7 segments in Microcoryphia but of 5–6 segments in Zygentoma; (d) praetarsi with two claws in Microcoryphia and three claws in most of Zygentoma (some genera of Zygentoma have also two claws; e.g. Hyperlepisma Silvestri, 1932, Mormisma Silvestri, 1938, and some other deserticolous genera); (e) metacoxae with styli in Microcoryphia but without styli in Zygentoma; (f) body more arched in Microcoryphia but more flattened in Zygentoma and (g) middle caudal filament always strongly longer than lateral two in Microcoryphia but inconspicuously longer or of the same length as lateral two in Zygentoma (see Kratochvíl 1959).

Identification key of Slovak species of Zygentoma

(For morphological structures, see Fig. 9)

1. Eyes absent. Scales present or not (family Nicoletiidae)….…….…………………………….……. 2

Eyes present. Scales always present (family Lepismatidae)…………………….…….….….… 4

2. Body short, spindle-shaped. Thorax broader than the abdomen. Golden scales. Myrmecophilic………………………………………………………………………………………Atelura formicaria

Body elongated and cylindrical. Thorax as broad as the abdomen. Scales absent. Often without pigmentation…………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………. 3

3. Urosternites I–VII divided into two lateral coxites and one median sternite…[Nicoletia phytophila].

Only urosternite I divided. Urosternites II–VII not divided and composed by a single plate………………………………………………………………………………………………….….[Coletinia maggi]

4. Macrosetae smooth, split into two or three ends apically. Head without tufts of macrosetae; few frontal setae arranged in irregular rows. Pronotum without a setal collar. Male paramera present………………………………………………………………………………………………Lepisma saccharinum

Macrosetae barbed. Head with tufts of abundant macrosetae (Figs. 4a and 7a). Pronotum with a setal collar (a row of macrosetae inserted on the anterior margin; see Figs. 4a and 7a). Male paramera absent………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………….…. 5

5. Urotergites with at most 2 + 2 bristle combs of macrosetae……………….…Thermobia domestica

At least urotergites II–V with 3 + 3 bristle combs of macrosetae (genus Ctenolepisma)….……… 6

6. Urotergite X short, subtriangular with a convex posterior border. Three pairs of abdominal styli in adults. Tibiae with lanceolate scales. Femora with lanceolate or subtriangular scales on their inner side. Anterior mesonotal trichobothria inserted in the second last lateral combs……. Ctenolepisma lineatum

Urotergite X trapezoidal, with straight or nearly straight posterior border. One or two pairs of abdominal styli. Tibiae without scales. Femora with rounded scales on their inner side. Anterior mesonotal trichobothria inserted in the third last lateral combs. Anthropophilic………………………. 7

7. Both sexes with two pairs of styli when adults (Figs. 2, 3 and 4d). Urotergite VI with 3 + 3 combs of macrosetae. Without pigment or scarcely yellowish pigmented, but dorsal scales usually dark greyish and with very dense ribs. Antennae and caudal filaments, when intact, as long or longer than the body length……………………………………………………….……Ctenolepisma longicaudatum (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4 and 8)

Both sexes with only one pair of abdominal styli when adults (Fig. 6). Urotergite VI with 2 + 2 combs of macrosetae. Uniformly whitish with a slightly yellowish-brown or grey pigment in some appendages. Dorsal scales almost hyaline and mostly with less dense ribs. The length of the antennae is an intraspecific variable but usually not longer than body length when intact. Two lateral caudal filaments approximately 2/3 of the body length, the middle caudal filament is approximately as long as the body when intact …….…………………………….……………………….Ctenolepisma calvum (Figs. 5, 6, 7 and 8)

Discussion

In particular, two non-native silverfish species (C. longicaudatum and C. calvum) have spread across Europe recently (Kulma et al. 2021, 2022; Querner et al. 2022) solely due to human activity. As these insects cannot survive the winter in most Central and Northern European climates, suitable living conditions are restricted to houses, museums, warehouses, archives and other buildings (Brimblecombe and Querner 2021; Querner et al. 2022). The frequency of new introductions has increased in recent years, so further spread should be expected. Both species are strictly synanthropic; no outdoor occurrences have been published, so climate does not limit their distribution. For this reason, they have also recently become successfully established in northern Europe (Aak et al. 2019; Sammet et al. 2021).

We agree with Kulma et al. (2021) that the current distribution of C. longicaudatum in Europe, in particular, is underestimated, as supported by findings published on social platforms (e.g. iNaturalist.org). Further collaboration between local entomologists, citizens and pest control services is essential to confirm the range of this non-native species.

The first record of C. longicaudatum in 2017 corresponds with records in Czechia, where the first occurrence of a population of C. longicaudatum was recorded in warehouses and around office buildings (Kulma et al. 2018). Subsequently, C. longicaudatum was recorded throughout the country over the next three years. As expected, dwellings emerged as the main habitats of the species, as confirmed by recent data from several countries. This phenomenon is known, for example, in the Faroe Islands, the Netherlands and Norway, where the species has become a notable household species (Thomsen et al. 2019; Querner et al. 2022; Hage et al. 2020). Four years later (2021), the silverfish C. calvum was also recorded in Slovakia, again in the same year as in the Czech Republic (Kulma et al. 2021). Since we assume that C. calvum spreads similarly to C. longicaudatum, it is possible that C. calvum was overlooked because it may have been mistaken for the juvenile stages of C. longicaudatum.

The extent of damage and current distribution in museums and archives in Slovakia has yet to be discovered, so it would be advisable to undertake more intensive mapping and monitoring (e.g. using sticky traps) to ascertain populations’ current distribution and status as quickly as possible. First, it is advisable to target archives, museums and libraries, for which these species pose the greatest threat concerning the valuable items deposited by these institutions (Querner et al. 2022).

Since Paclt’s work (Paclt 1959), no comprehensive work or species list of Slovak silverfish (specifically of the family Lepismatidae) has been published, so we decided to fill this gap of more than sixty years. Since Kratochvíl’s identification key for identifying Zygentoma and Microcoryphia of former Czechoslovakia (Kratochvíl 1959), keys were never actualised or provided for Slovakian Zygentoma until now. Some useful but old keys exist for British Delaney (1954) and Polish species (Stach 1955).

Notes on the identification of the species

During microscopic studies of specimens, we noticed that the rib density of scales varies between the species. Therefore, we photographed various shapes and sizes of scales under a brightfield microscope. Selected photos of scales are presented in Fig. 4. and Fig. 7. Comparison of C. calvum and C. longicaudatum scale rib densities are shown in Fig. 8. As can be seen, C. longicaudatum has significantly higher rib density than C. calvum (14 vs. 43 ribs per 100 μm for larger scales and 41 vs. 74 ribs for smaller scales). However, we would not like to present exact numbers as the scales are from various body parts and only from two specimens. Further study is required; however, the rib density is so distinct that we have included it in the key. In future studies, this could be a helpful identification character for separating other members of Lepismatidae.

Although C. calvum is distinctly smaller than C. longicaudatum in Slovakia, according to our studied specimens (maximum length 8 mm in C. calvum and 11 mm in C. longicaudatum), the body length of C. calvum can vary, and it can reach 12 mm, as it was discovered in Japan by Shimada et al. (2022).

The presence of two pairs of styli in males of C. longicaudatum (Fig. 4d) is also an important character distinguishing the species from another visually similar synanthropic species, C. targionii (Grassi and Rovelli, 1889), males of which have only one pair of styli (e.g. Molero-Baltanás et al. 2015). Nevertheless, this Mediterranean species was introduced only in the USA and India until now (Wygodzinsky 1972; Hazra and Mandal 2007), and its spreading within Europe northwards from the Mediterranean area is still unknown.

References

Aak A, Rukke BA, Ottesen PS (2019) Long-tailed silverfish (Ctenolepisma longicaudata) – biology and control. Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Oslo

Brimblecombe P, Querner P (2021) Silverfish (Zygentoma) in austrian museums before and during COVID-19 lockdown. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 164:105296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibiod.2021.105296

Christian E (1993) Insekten entlang des urbanen Gradienten: Beispiele aus Wien. Schriften des Vereins zur Verbreitung Naturwissenschaftlicher Kenntnisse Wien 132:195–206

Christian E (1994) Atelura formicaria (Zygentoma) follows the pheromone trail of Lasius niger (Formicidae). Zool Anz 232:213–216

Claus R, Vantieghem P, Molero-Baltanás R, Parmentier T (2022) Established populations of the indoor silverfish Lepisma saccharinum (Insecta: Zygentoma) in red wood ant nests. Belg J Zool 152:45–53. https://doi.org/10.26496/bjz.2022.98

Crusz H (1957) Gregarine protozoa of silverfish (Insecta: Thysanura) from Ceylon and England, with the recognition of a new genus. J Parasitol 43:90–92. https://doi.org/10.2307/3274766

Delaney MJ (1954) Thysanura and Diplura. Handbooks for the identification of british insects. Vol. 1. Part 2. Royal Entomological Society of London, London

Ferianc O (1975) Slovenské mená hmyzu. VEDA, Vydavateľstvo Slovenskej akadémie vied, Bratislava

Franc V, Majzlan O, Krištín A, Wiezik M (2015) On the distribution and ecology of the ant cricket (Myrmecophilus acervorum) (Orthoptera: Myrmecophilidae) in Slovakia. In: Alberty R (ed) Proceeding of the conference “Roubal’s Days I”, Matthias Belivs University Proceedings – Biological series, 5 (Supplementum 2), Banská Bystrica, pp 40–50

Gilgado JD, Bobbitt I, Molero-Baltanás R, Braschler B, Gaju-Ricart M (2021) Erstnachweis von Nicoletia phytophila Gervais, 1844 (Zygentoma, Nicoletiidae) in Gewächshäusern in der Schweiz. Entomo Helv 14:113–116

Hage M, Rukke BA, Ottesen PS, Widerøe HP, Aak A (2020) First record of the four-lined silverfish, Ctenolepisma lineata (Fabricius, 1775) (Zygentoma, Lepismatidae), in Norway, with notes on other synanthropic lepismatids. Norw J Entomol 67:8–14

Hazra AK, Mandal GP (2007) Pictorial handbook on indian Thysanura. Zoological Survey of India, Kolkata

iNaturalist (n.d.). https://www.inaturalist.org. Accessed 15 Jan 2023

Kratochvíl J (1945) Naše šupinušky se zvláštním zřetelem na moravská chráněná území. Unsere Thysanuren, mit Rücksicht auf die Fauna der mährischen Schutzgebiete. Entomologické Listy (Folia Entomologica) 8:41–67

Kratochvíl J (1959) Řád šupinušky – Thysanura. In: Kratochvíl J (ed) Klíč zvířeny ČSR. Díl III. Československá Akademie Věd, Praha, pp 133-142

Krumpál M, Krumpálová Z, Cyprich D (1997) Bezstavovce (Evertebrata) skleníkov Bratislavy (Slovensko). Entomofauna Carpath 9:102–106

Kulma M, Vrabec V, Patoka J, Rettich F (2018) The first established population of the invasive silverfish Ctenolepisma longicaudata (Escherich) in the Czech Republic. BioInvasions Records 7:329–333. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2018.7.3.16

Kulma M, Bubová T, Davies MP, Boiocchi F, Patoka J (2021) Ctenolepisma longicaudatum Escherich (1905) became a common pest in Europe: case studies from Czechia and the United Kingdom. Insects 12:810. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12090810

Kulma M, Molero-Baltanás R, Petrtýl M, Patoka J (2022) Invasion of synanthropic silverfish continues: first established populations of Ctenolepisma calvum (Ritter, 1910) revealed in the Czech Republic. BioInvasions Records 11:110–123. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2022.11.1.12

Landsberger B, Querner P (2018) Invasive Fischchen (Insecta, Zygentoma) in Deutschland und Österreich. Neue Heurausforderungen im integrierten Schädlingsmanagement. Archivar 71:328–332

Majzlan O (2009) Rozšírenie svrčíka mraveniskového Myrmecophilus acervorum (panzer, 1799) na Slovensku. Natura Carpatica 50:147–152

Mendes LF (2002) Taxonomy of Zygentoma and Microcoryphia: historical overview, present status and goals for the new millennium. Proceedings of the 10th International Colloquium on Apterygota, České Budějovice 2000: Apterygota at the beginning of the third millennium. Pedobiologia 46:225–233. https://doi.org/10.1078/0031-4056-00129

Misof B, Liu S, Meusemann K, Peters RS, Donath A, Mayer C, Frandsen PB, Ware J, Flouri T, Beutel RG et al (2014) Phylogenomics resolves the timing and pattern of insect evolution. Science 345:763–767. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1257570

Molero R, Tahami MS, Gaju M, Sadeghi S (2018) A survey of basal insects (Microcoryphia and Zygentoma) from subterranean environments of Iran, with a description of three new species. ZooKeys 806:17–46. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.806.27320

Molero-Baltanás R, Fanciulli PP, Frati F, Carapelli A, Gaju-Ricart M (2000) New data on the Zygentoma (Insecta, Apterygota) from Italy. Proceedings of 5th International Seminar on Apterygota, Cordoba 1998. Pedobiologia 44:320–332. https://doi.org/10.1078/S0031-4056(04)70052-9

Molero-Baltanás R, Gaju Ricart M, Bach de Roca C (2012) New data for a revision of the genus Ctenolepisma (Zygentoma: Lepismatidae): redescription of Ctenolepisma lineata and new status for Ctenolepisma nicoletii. Ann Soci Entomol France 48:66–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/00379271.2012.10697753

Molero-Baltanás R, Gaju-Ricart M, Bach de Roca C (2015) Actualización del conocimiento del género Ctenolepisma Escherich, 1905 (Zygentoma, Lepismatidae) en España peninsular y baleares. Bol Asoc Esp Entomol 39:356–390

Molero-Baltanás R, Gaju-Ricart M, Fišer Ž, Bach de Roca C, Mendes LF (2022) Three new species of european Coletinia Wygodzinsky (Zygentoma, Nicoletiidae), with additional records and an updated identification key. Eur J Taxon 798:127–161. https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2022.798.1675

Paclt J (1951) O půdní zvířeně ČSR. I. Contribution a l’etude de notre faune du domaine principalement endoge. I Entomologické Listy (Folia Entomol) 14:161–164

Paclt J (1956) Apterygota Žitného ostrova. Biológia 9:352–357

Paclt J (1959) K faune šupinaviek (Thysanura) Slovenska. Biológia 14:433–436

Paclt J (1963) Thysanura Fam Nicoletiidae. Genera Insectorum 216:1–58

Paclt J (1967) Thysanura. Fam. Lepidotrichidae, Maindroniidae. Lepismatidae Genera Insectorum 218e:1–86

Paclt J (1979) Neue Beiträge zur Kenntnis der Apterygoten-Sammlung des Zoologischen Instituts und Zoologischen Museums der Universität Hamburg. VI. Weitere Doppel- und Borstenschwänze (Diplura: Campodeidae; Thysanura: Lepismatidae und Nicoletiidae). Ent Mitt Zool Mus Hamburg 105:221–228

Paclt J, Christian E (1996) Die Gattung Coletinia in Mitteleuropa (Thysanura: Nicoletiidae). Deutsch Entomol Ztschr 43:275–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/mmnd.19960430211

Pekár S (2004) Predatory behavior of two european ant-eating spiders (Araneae, Zodariidae). J Arachnology 32:31–41. https://doi.org/10.1636/S02-15

Petricskó J (1892) Selmeczbánya vidéké állattani tekintetben. Selmeczbányai gyógyászati és természettudományi egyesület. Selmeczbánya [= Banská Štiavnica]

Pothula R, Shirley D, Perera OP, Klingeman WE, Oppert C, Abdelgaffar HMY, Johnson BR, Jurat-Fuentes JL (2019) The digestive system in Zygentoma as an insect model for high cellulase activity. PLoS ONE 14:e0212505. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212505

Querner P, Sterflinger K (2021) Evidence of Fungal spreading by the Grey Silverfish (Ctenolepisma longicaudatum) in austrian museums. Restaurator Int J Preservation Libr Arch Mater 42:57–65. https://doi.org/10.1515/res-2020-0020

Querner P, Szucsich N, Landsberger B, Erlacher S, Trebicki L, Grabowski M, Brimblecombe P (2022) Identification and spread of the ghost silverfish (Ctenolepisma calvum) among museums and homes in Europe. Insects 13:855. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects13090855

Ritter W (1910) Neue Thysanuren und Collembolen aus Ceylon und Bombay, gesammelt von Dr. Uzel. Ann Naturhist Mus Wien 24:379–398

Robla J, Gaju-Ricart M, Molero-Baltanás R (2023) Assessing the diversity of ant-associated silverfish (Insecta: Zygentoma) in Mediterranean countries: the most important hotspot for Lepismatidae in Western Palaearctic. Diversity 15:635. https://doi.org/10.3390/d15050635

Rusek J (1977) Protura, Collembola, Diplura, Thysanura. Enumeratio Insectorum Bohemoslovakiae. Acta Faun Entomol Musei Natl Pragae (Supplementum 4):9–10

Sammet K, Martin M, Kesküla T, Kurina O (2021) An update to the distribution of invasive Ctenolepisma longicaudatum Escherich in northern Europe, with an overview of other records of Estonian synanthropic bristletails (Insecta: Zygentoma). Biodivers Data J 9:e61848. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.9.e61848

Shimada M, Watanabe H, Komine Y, Sato Y (2022) New records of Ctenolepisma calvum (Ritter, 1910) (Zygentoma, Lepismatidae) from Japan. Biodivers Data J 10:e90799. https://doi.org/10.3897/BDJ.10.e90799

Smith GB (2017) The australian silverfish fauna (order Zygentoma) – abundant, diverse, ancient and largely ignored. Gen Appl Entomol 45:9–58

Smith GB, Mitchell A (2019) Species of Heterolepismatinae (Zygentoma: Lepismatidae) found on some remote eastern australian islands. Rec Aust Mus 71:139–181. https://doi.org/10.3853/j.2201-4349.71.2019.1719

Stach J (1922) Apterygoten aus dem nordwestlichen Ungarn. Ann Mus Natl Hung 19:1–75

Stach J (1929) Verzeichnis der Apterygogenea Ungarns. Ann Mus Natl Hung 26:269–312

Stach J (1955) Klucze do oznaczania owadów Polski. Część III–V. Pierwogonki – Protura, Widłogonki – Diplura, Szczeciogonki – Thysanura. Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, Warszawa

Štys P (1977) Faunistic records from Czechoslovakia. Thysanura. Lepismatidae. Heteroptera. Miridae. Acta Entomol Bohemoslovaca 74:63

Theron JG (1963) The domestic fish moths of South Africa (Thysanura: Lepismatidae). South Afr J Agric Sci 6:125–130

Thomsen E, Dahl HA, Mikalsen SO (2019) Ctenolepisma longicaudata (Escherich, 1905): a common, but previously unregistered, species of silverfish in the Faroe Islands. BioInvasions Records 8:540–550. https://doi.org/10.3391/bir.2019.8.3.09

Tömösváry Ö (1884) Adatok hazánk Thysanura-faunájához. Mathematikai és Természettudományi Közlemények, Budapest

Trematerra P, Pinniger D (2018) Museum pests–cultural heritage pests. In: Athanassiou CG, Arthur FH (eds) Recent advances in stored product protection. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, pp 229–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-56125-6_11

Uzel J (1891) Šupinušky země české. Věstník České Společnosti Nauk. Třída mathematicko-přírodovědná 2:3–82

Uzel J (1897) Vorläufige Mitheilung über die Entwicklung der Thysanuren. Zool Anz 20:125–132

Uzel J (1898) Studien über die Entwicklung der apterygoten Insekten. Königgrätz

Vellay E (1899) Ordo Apterygogenea. In: Paszlavszky J (ed) A Magyar birodalom állatvilága. A Magyar birodalomból eddig ismert állatok rendszeres lajstroma. Fauna Regni Hungariae. Animalium Hungariae hucusque cognitorum enumeratio systematica. A Királyi Magyar Természettudományi Társulat [= Royal Hungarian Natural History Society], Budapest, pp 19–22

Weidner H (1983) Nach Hamburg eingeschleppte Collembola und Zygentoma. Anz Schädlingskd Pfl Umwelt 56:105–107

Wygodzinsky PW (1972) A review of the silverfish (Lepismatidae, Thysanura) of the United States and the Caribbean area. Am Mus Novit 2481:1–26

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to the reviewers for their dedication and efforts. We are especially thankful to reviewer #2 for their insightful, beneficial, and thorough feedback and suggestions, which extensively enhanced the manuscript’s original content. We express our gratitude to Ľubomír Haluška and Matúš Gonšor for collecting some specimens and Nikolaus Szucsich for identifying the specimens on the iNaturalist website. We would like to acknowledge Ľubomír Vidlička from the Institute of Zoology, Slovak Academy of Sciences, for his invaluable help in finding historical data on the distribution of silverfish in Slovakia.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic in cooperation with Centre for Scientific and Technical Information of the Slovak Republic The research was financially supported by the project agencies VEGA (Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education, Science, Research and Sport of the Slovak Republic and the Slovak Academy of Sciences): project VEGA no. 2/0108/21 and APVV (The Slovak Research and Development Agency): project no. APVV-19-0134 and APVV-21-0386.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bednár, F., Hemala, V. & Čejka, T. First records of two new silverfish species (Ctenolepisma longicaudatum and Ctenolepisma calvum) in Slovakia, with checklist and identification key of Slovak Zygentoma. Biologia 79, 425–435 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11756-023-01526-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11756-023-01526-z