At A Glance

- Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP) is a systemic autoimmune inflammatory disease and is a subset of mucous membrane pemphigoid that occurs in 1/10,000 to 1/50,000 individuals. It disproportionately affects women at a ratio of approximately 2:1 with no racial predilection.

- OCP often requires a multidisciplinary approach between dry eye, uveitis, and oculoplastic specialists.

- The primary objective in managing OCP is to halt progression.

Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (OCP) poses a unique management challenge to eye care practitioners and often requires a multidisciplinary approach between dry eye, uveitis, and oculoplastic specialists. This cicatrizing conjunctivitis results in an abnormal ocular surface and eyelid anatomy, leading to an unstable tear reservoir, reduced tear drainage, poor blink mechanics, exposure keratopathy, and cicatricial entropion with trichiasis. Understanding the disease process is crucial to effectively managing ocular surface disease (OSD) related to OCP. This article aims to assist clinicians in identifying early OCP-induced anatomic changes and better topically managing OCP-related OSD.

SIGNS, SYMPTOMS, AND DIAGNOSIS

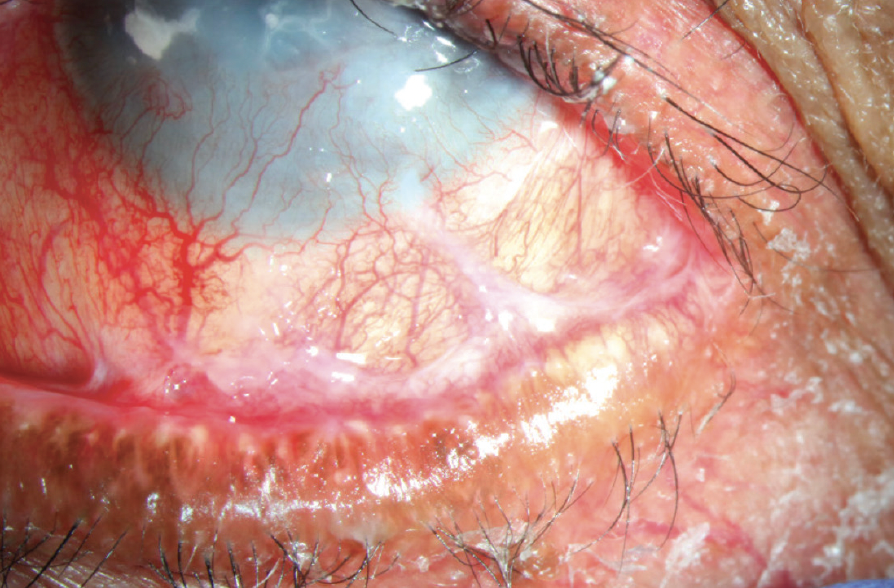

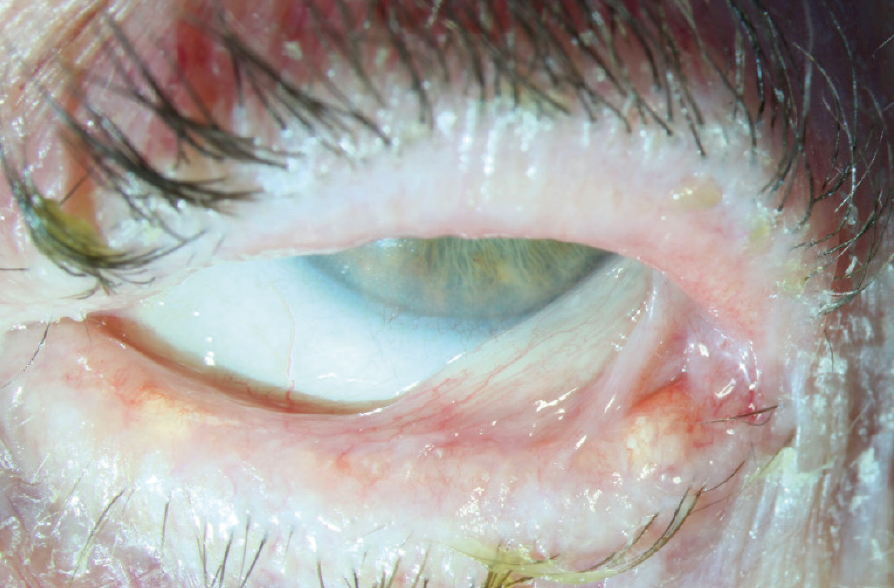

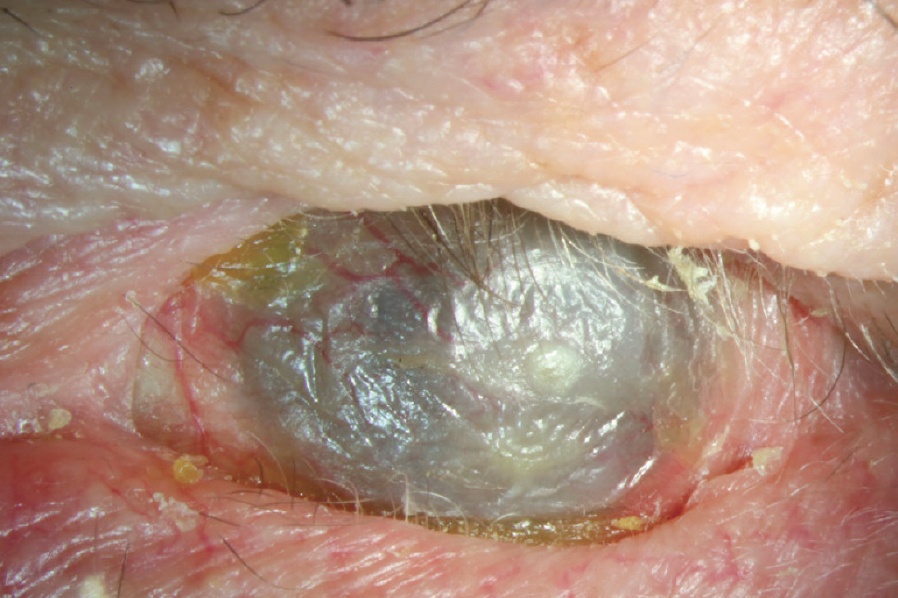

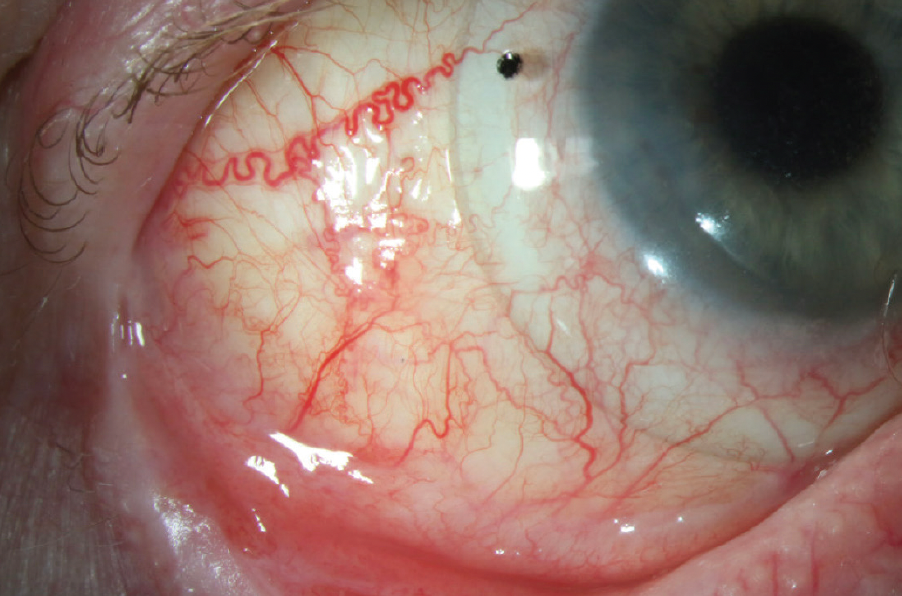

OCP is a systemic autoimmune inflammatory disease and is a subset of mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) that occurs in 1/10,000 to 1/50,000 individuals (Figures 1-9).1 It disproportionately affects women at a ratio of approximately 2:1 with no racial predilection.2 The linear deposition of immunoglobulin (Ig) A, IgC, and C3 in the epithelial basement membrane of the conjunctiva characterizes the disease. This deposition results in conjunctival scarring, inferior fornix shortening, and symblepharon.3 Conjunctival scarring may also cause cicatricial entropion and trichiasis, and in later stages, vision loss may occur due to limbal stem cell deficiency and central corneal opacification. End-stage OCP includes ankyloblepharon.

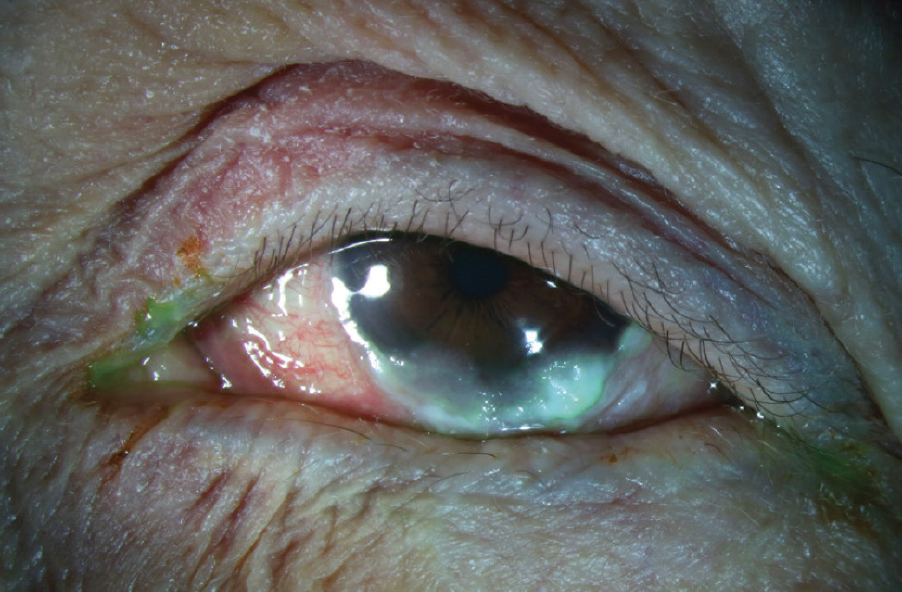

Figure 1. This case of end-stage OCP exhibited severe fornix shortening, cicatricial entropion of each lid, and dense ocular surface keratinization.

(Image courtesy of Amit Reddy, MD.)

Figure 2. Stage 3 OCP with temporal symblepharon and two early nasal symblephara.

(Image courtesy of Amit Reddy, MD.)

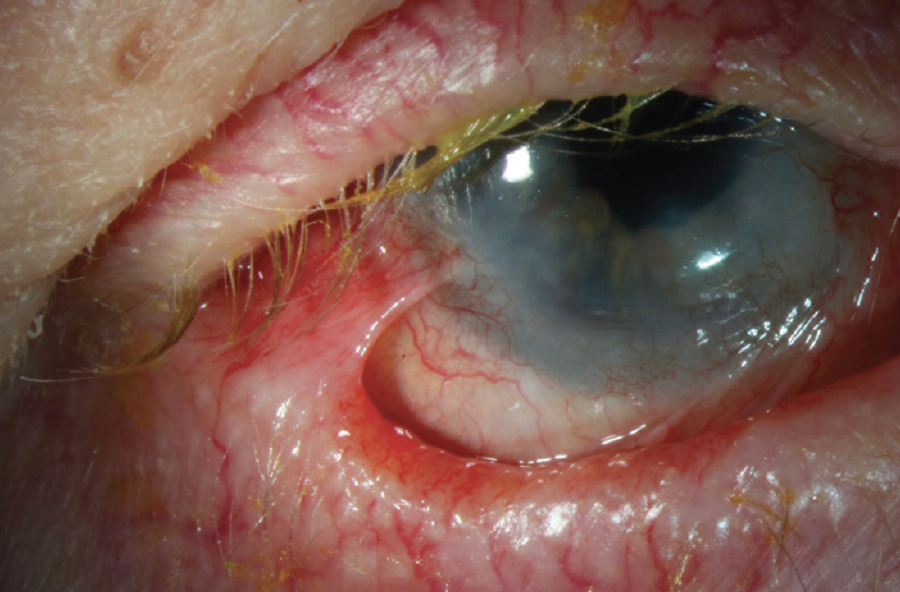

Figure 3. Fornix shortening, symblephara, corneal neovascularization, and superior cicatricial entropion in late-stage OCP.

(Image courtesy of Amit Reddy, MD.)

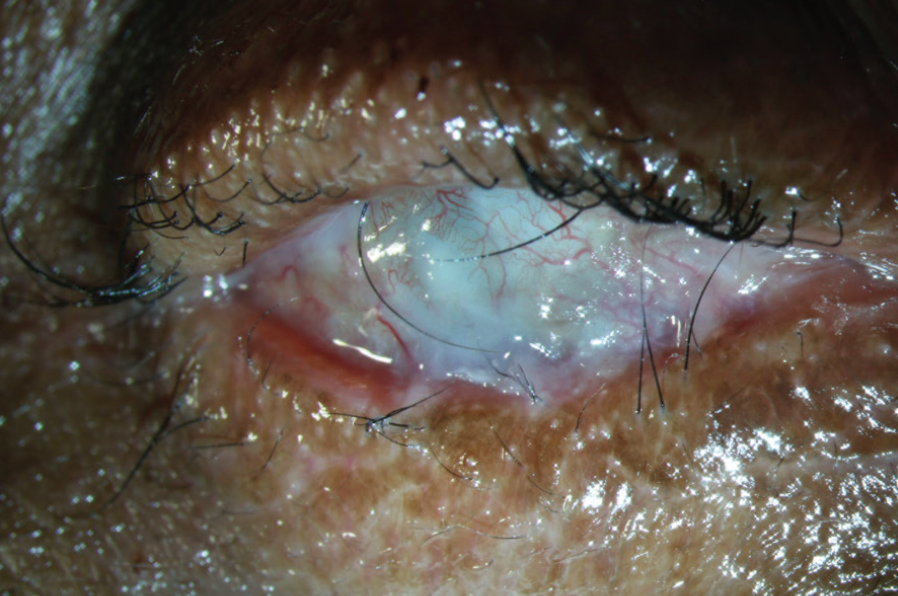

Figure 4. Late-stage OCP with possible ankyloblepharon and advanced symblephara.

(Image courtesy of Amit Reddy, MD.)

Figure 5. End-stage OCP with severe ocular surface keratinization, corneal neovascularization, and cicatricial entropion of each lid.

(Image courtesy of Amit Reddy, MD.)

Figure 6. Scleral lens wear in a patient with OCP, fornix shortening, and conjunctival fibrosis.

(Image courtesy of Amit Reddy, MD.)

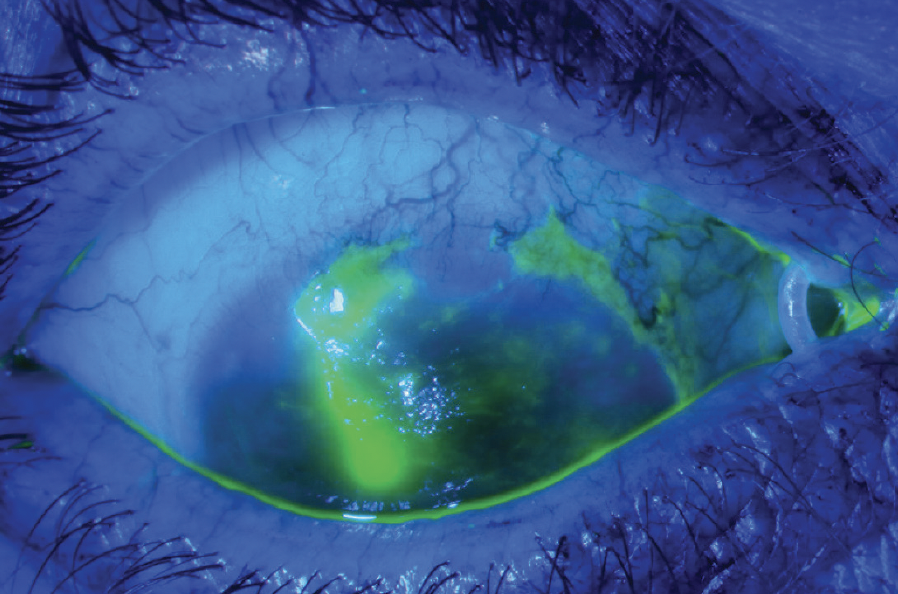

Figure 7. Epithelial defect secondary to limbal stem cell deficiency in a patient with OCP and ocular rosacea.

(Image courtesy of Amit Reddy, MD.)

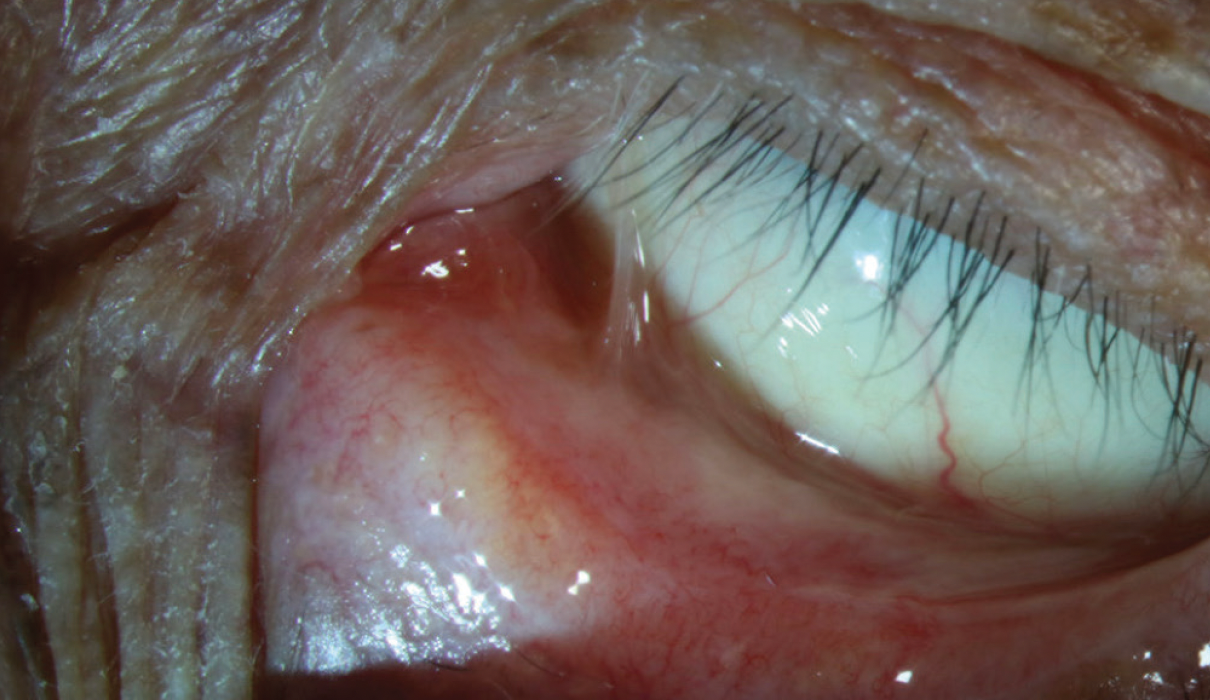

Figure 9. Nasal symblepharon and inferior conjunctival fibrosis with fornix shortening.

(Image courtesy of Amit Reddy, MD.)

OCP is often misdiagnosed initially due to its nonspecific symptoms and insidious nature.4 Early symptoms, such as redness, tearing, burning, foreign body sensation, or photophobia, may resemble those of dry eye disease. Although these symptoms may be partially alleviated with the use of artificial tears, warm compresses, topical immunomodulators, and punctal plugs, OCP will progress without systemic immunosuppression. If conjunctival fibrosis with inferior fornix shortening is observed, other conditions should be considered prior to making a diagnosis of OCP. The differential diagnosis for OCP includes a history of Steven-Johnson Syndrome or toxic epidermal necrolysis, trachoma, graft versus host disease, sequelae from trauma (eg, chemical, thermal, radiation), medicamentosa (especially from glaucoma drops), Sjögren syndrome, adenoviral keratoconjunctivitis, ocular rosacea, sarcoidosis, and anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis. The presence of a progressing symblepharon is a clinically differentiating feature of OCP, which only rarely occurs in cases of lichen planus, neoplasia, and paraneoplastic pemphigus.5,6

A thorough history should include questions about prior ocular trauma, ocular conditions, ocular surgeries, autoimmune conditions, and malignancies. Inquiring about sores or irritation of other mucous membranes is helpful, as MMP may involve mucous membranes of the mouth, trachea, esophagus, anus, urethra, and vagina. The gold standard for confirming OCP is a conjunctival biopsy and direct immunofluorescence demonstrating linear deposition of IgA, IgG, or C3 in the epithelial basement membrane zone. However, the literature reports a high rate of false negatives (~40%); therefore, a negative finding does not preclude a diagnosis of OCP.5,7-9 Sampling tissue from areas of active inflammation is more likely to yield a definitive diagnosis of OCP.10 In cases of progressive conjunctival scarring, fornix shortening, and symblepharon formation, there should be a high suspicion for OCP even in a negative conjunctival biopsy setting. Recent reports suggest that a biopsy of oral buccal mucosa can help diagnose MMP, even in the absence of oral symptoms.7

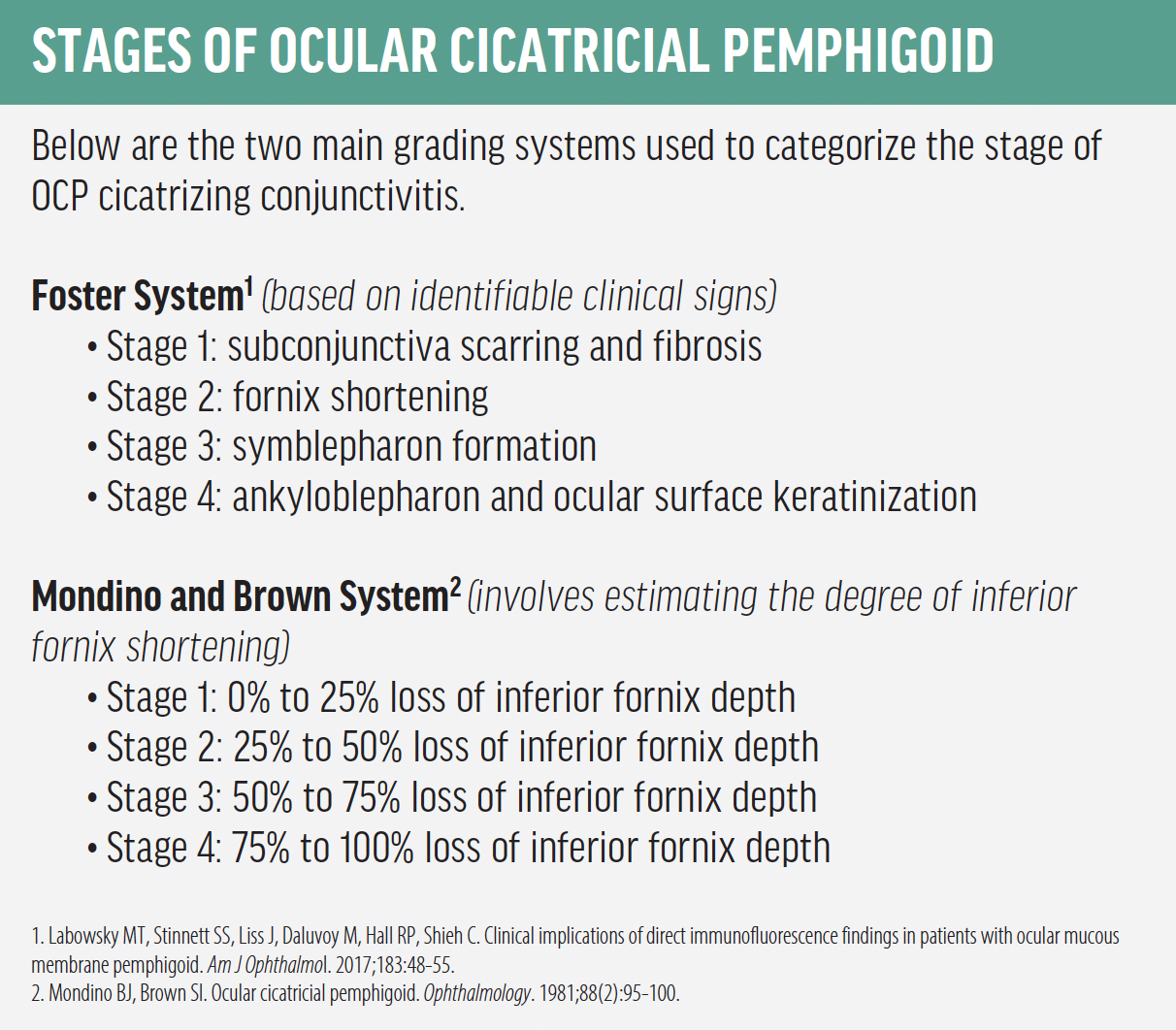

There are two main grading systems used to categorize the stage of OCP cicatrizing conjunctivitis: the Foster System, which is based on identifiable clinical signs, and the Mondino and Brown System, which involves estimating the degree of inferior fornix shortening (see Stages of Ocular Cicatricial Pemphigoid).5,11 The next step is determining a treatment plan.

TREATMENT GOALS & OPTIONS

The primary objective in managing OCP, as well as other cases of cicatrizing conjunctivitis, is to halt its progression using systemic immunomodulatory therapy (IMT). Topical treatment alone is insufficient and ineffective in managing OCP, as cicatrizing conjunctivitis will progress. Severe cicatricial changes further complicate OSD management. Anatomic alterations of the conjunctiva, tear film, and eyelids present challenges for management of this OSD and often require early and aggressive treatment options, such as autologous serum eye drops and topical immunomodulators. A multidisciplinary approach is likely warranted, involving OSD and uveitis specialists with a low threshold to involve an oculoplastics provider. Although managing OSD is vital in stabilizing vision and minimizing ocular symptoms, the goal of controlling progression should be primary.

Because OCP is a systemic autoimmune inflammatory disease, systemic therapy is vital in halting conjunctival fibrosis progression. The choice of IMT is dependent on the stage and rate of advancement. In mild cases, dapsone, a sulfonamide antibiotic with antiinflammatory and immunomodulatory properties, may be used.10 Steroid-sparing agents, such as methotrexate; mycophenolate mofetil; or azathioprine; are often used in moderate cases.10 Such treatments are often used with a temporary systemic corticosteroid pulse therapy because many systemic therapies require several months to become effective. Rituximab, intravenous immunoglobulin, or etanercept are usually reserved for cases of rapid progression or poor response to conventional therapies.10 Surgeries may be necessary for eyelid ablation, entropion repair, lateral tarsorrhaphy, or limbal stem cell transfer.5

OSD is a prevalent comorbidity associated with OCP, and it poses a significant management challenge. Traditional treatments, such as topical lubricants, warm compresses, and lifestyle modifications, are generally inadequate in addressing both symptomology and surface disease.

Topical immunomodulatory agents, such as cyclosporine or lifitegrast ophthalmic solution 5% (Xiidra, Novartis), are frequently successful in reducing surface inflammation associated with OCP. Although these agents can aid in controlling inflammation, mild corticosteroids, such as fluorometholone or loteprednol, may also help address surface inflammation. However, due to the inherent risks and complications of prolonged corticosteroid use, it is preferable to use the minimum effective dose for controlling inflammation. It is necessary to ensure careful monitoring of IOP, and phakic patients should be warned about the possibility of cataract formation. Moreover, long-term corticosteroid use is generally not advisable for patients with glaucoma.

Autologous serum eye drops are a particularly effective treatment option for patients with OCP due to the aqueous deficiency component of their dry eye resulting from cicatricial changes to the ocular surface or a highly unstable tear film caused by these anatomic changes. As a result, nutritional components that are typically present in the tear film may be insufficient in patients with OCP. Autologous serum eye drops can provide essential nutritional support to the cornea in the form of growth factors, lactoferrin, fibronectin, albumin, lysozymes, immunoglobulins, and vitamin A.

Although scleral lenses are typically an excellent treatment modality for OSD, they are not always feasible for patients with OCP due to the patient’s highly irregular conjunctival anatomy, symblephara, and narrow palpebral fissures. In mild or moderate cases of OCP, scleral lens fitting may be possible, but these patients are generally less symptomatic and their OSD may be controlled with topical medications alone. Limbal stem cell deficiency may occur in more advanced cases of OCP, in which case bandage contact lenses or amniotic membrane transplantation may be used.

Although punctal plugs could be used as a treatment option for dry eye in patients with OCP to increase the tear reservoir, they are rarely used for two reasons. First, in our clinical experience, patients with OCP are already more likely to experience epiphora due to insufficient drainage secondary to abnormal eyelid anatomy. Punctal plugs may worsen this. Second, one of the challenges in treating OCP is controlling surface inflammation, and punctal plugs should be avoided in cases where ocular surface inflammation persists.

TAKEAWAYS

Understanding the OCP disease process is key in effectively managing the related OSD. It’s important to remember that this also presents a unique and complex challenge, and that a multidisciplinary approach is likely needed when approaching such cases. The most important person is the uveitis specialist (or rheumatologist) who halts progression through systemic immunomodulation. An OSD specialist is also very helpful, and an oculoplastics provider may be needed if the patient needs eyelid surgery. Ultimately, the primary goal should be to control disease progression.

The author would like to thank Amit Reddy, MD, of the University of Colorado School of Medicine, for reviewing and editing this article.

- 1. Weisenthal R, Afshari N, Bouchard C, Colby K, Rootman D, Tu E. Section 8: External Disease and Cornea. 2016-2017 Basic and Clinical Science Course (BCSC). 2016.

- 2. Stan C, Diaconu E, Hopirca L, Petra N, Rednic A, Stan C. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2020;64(2):226-230.

- 3. Chan LS, Ahmed AR, Anhalt GJ, et al. The first international consensus on mucous membrane pemphigoid: definition, diagnostic criteria, pathogenic factors, medical treatment, and prognostic indicators. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138(3):370-379.

- 4. Xu HH, Werth VP, Parisi E, Sollecito TP. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57(4):611-630.

- 5. Labowsky MT, Stinnett SS, Liss J, Daluvoy M, Hall RP, Shieh C. Clinical implications of direct immunofluorescence findings in patients with ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;183:48-55.

- 6. De Rojas MV, Dart JK, Saw VP. The natural history of Stevens–Johnson syndrome: patterns of chronic ocular disease and the role of systemic immunosuppressive therapy. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91(8):1048-1053.

- 7. Lopez SN, Cao J, Casas de Leon S, Dominguez AR. Utility of direct immunofluorescence using buccal mucosal biopsies in those with suspected isolated ocular mucous membrane pemphigoid. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(10):1171-1176.

- 8. You JY, Eberhart CG, Karakus S, Akpek EK. Characterization of progressive cicatrizing conjunctivitis with negative immunofluorescence staining. Am J Ophthalmol. 2020;209:3-9.

- 9. Branisteanu DC, Stoleriu G, Branisteanu DE, et al. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid (review). Exp Ther Med. 2020;20(4):3379-3382.

- 10. Wang K, Seitzman G, Gonzales JA. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2018;29(6):543-551.

- 11. Mondino BJ, Brown SI. Ocular cicatricial pemphigoid. Ophthalmology. 1981;88(2):95-100.