In part 1 we discussed the early career of this Parisian luthier, who lived in a politically troubled era under three different successive regimes: the Revolution, the Empire and the Restoration. But he also worked at a time during which French lutherie was completely transformed, as we shall see.

At the beginning of the 19th century we find Pique in a very different situation. A few years after his marriage he had become a father to two little girls: Agnes was born in 1793; Sophie the following year. A decade later, in 1805, a son was born, Louis, who was to be his expected successor. As a father of three aged 47, Pique worked hard producing a steady flow of instruments and, presumably judging it useful to have some spare money, sold two of his properties. Then follows silence for a few years.

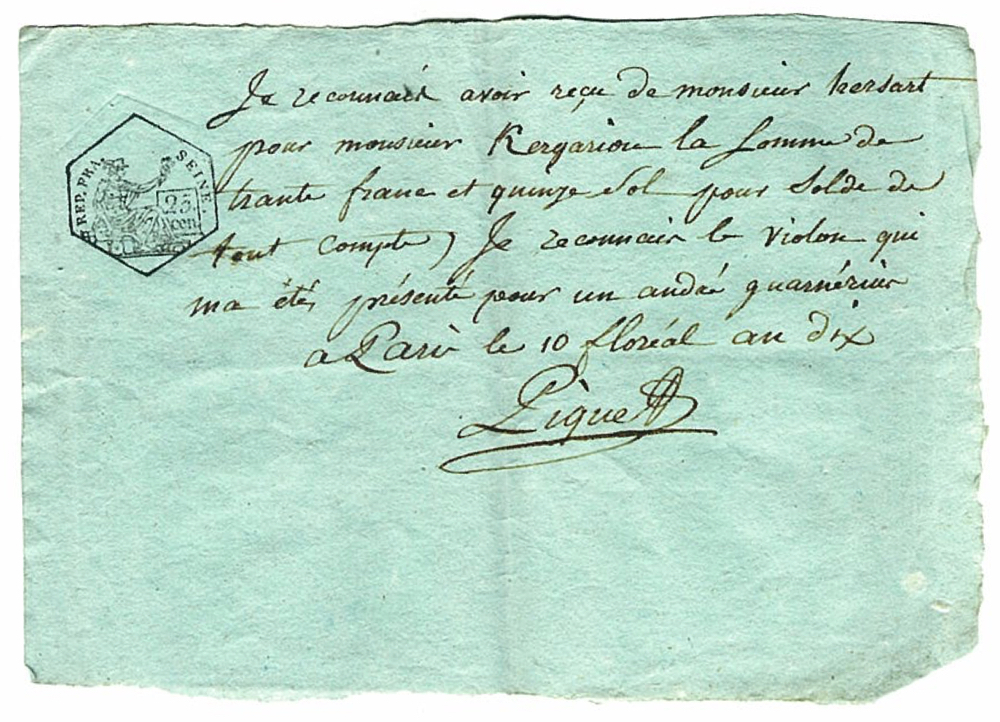

Pique’s signature on a letter from 1802 referring to an Andrea Guarneri violin

We rediscover him on March 13, 1813, when his younger daughter, Sophie, married a certain Sébastien Arnould Meysenberg. This fact is not without importance, because Meysenberg was the son of a piano maker, himself a piano teacher, and was to found a printing house that allowed him some independence. This therefore broadened the circle in which Pique moved.

By 1818 Pique had turned 60. At this point he decided to retire to a country house he had purchased a few years earlier in Charenton Saint Maurice, on the banks of the River Marne. His family having grown up, he had the two small original pavilions replaced by a two-storey house, then moved his furniture there. He converted the ground floor into a salon de réception with many tables for playing dames, trictrac, bouillon and dominos, reflecting the passion of the time for board games. He also worked on the two-hectare land around his estate, creating a pleasure garden, lined with orange and laurel trees in green-painted wooden boxes, then a vegetable garden with fruit trees and vines.

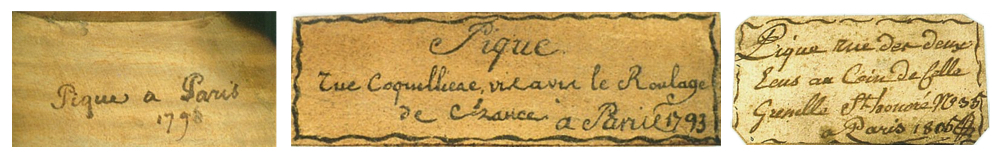

Pique’s signature inside a violin and labels from 1793 and 1806 showing his different addresses

In 1822 Pique’s elder daughter, Agnes, married Nicolas Antoine Lété, an instrument seller who had started out by doing what was called in his native city of Mirecourt, ‘the commerce of the islands’, which is to say he sold diverse merchandise including wood, instruments, lace and souvenirs from Lorraine, to Havana and the Antilles. He had moved to Paris in 1821 and opened a shop there selling instruments, strings and other items. In one advert in a business almanac from the 1820s he described himself as ‘Picq’s successor’ (Pique’s son, Louis, had chosen to become a magistrate with the Seine court of law rather than taking up violin making as a profession).

But sickness was catching up. Just a few months after Agnes’s wedding, Pique was unable to sign a document concerning the sale of a property, due to the loss of use of his right arm, which had also forced him to ask the notary to visit him at home with the documentation. Ten days later, on October 25, 1822, he was dead.