Salutations, BugFans,

The Field Guide to Insects of North America by Eaton and Kaufman includes a small sampling of non-insect Arthropods. In it, the authors state that jumping spiders are “as cute as spiders get,” and the BugLady totally agrees. It’s easy to wax anthropomorphic about jumping spiders, because when we stare at them, they stare straight back through 8 more-or-less forward-looking eyes. And we get plenty of chances to stare at them, because jumping spiders are very common outdoors and are not averse to coming indoors. They are bold, colorful, diurnal (day-time) hunters with plenty of “attitude.” The BugLady’s mailbox jumping spiders eat the mailbox ants and mailbox earwigs that try to settle there.

Jumping Spiders

Jumping spiders (JSs) are true spiders in the family Salticidae, in the order Araneae, in the class Arachnida, in the phylum Arthropoda. The family is a large one, including about 5,000 species worldwide, or about 13% of spider species. Some 300 of those species call the U.S. home. This isn’t their first rodeo; jumping spiders have decorated the planet for about 50 million years and can be found preserved in Baltic amber. Jumping spiders can tolerate a wide range of habitats from the very dry to the very wet and from intertidal zones to mountains, but their hearts are in the tropical forests.

How do you know if it’s a JS that’s returning your gaze? The gaze itself is accomplished with 8 eyes that are arranged in 3 rows (some authors describe the arrangement as 2 down-curved lines, like 2 “upside-down smiles.”). Two large, forward-facing eyes (the better to see you with, my dear) allow the same type of binocular vision that is enjoyed by birds of prey. Some of the remaining eyes also face forward, and others angle upwards. Bottom line—the JSs can turn its head 45 degrees and can see 360 degrees. It is said to be able to identify prey up to a foot away, and its communication with other spiders depends mostly on visual cues.

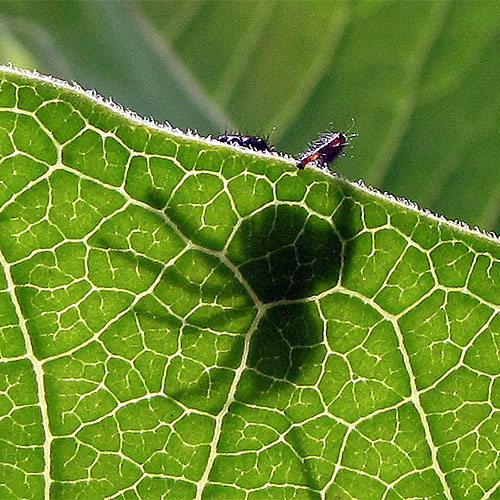

JS’s are relatively short-legged. Each leg ends with many tiny hairs, and each of those tiny hairs is further split into many more hairs, and each of those hairs is equipped with an “end foot.” With all those mini-feet, jumping spiders can boldly go where no spider has gone before—like straight up a pane of glass with the end feet gripping, just like a climbing wall, the “imperfections” in the glass.

JSs don’t spin webs to capture their prey; when they spot a potential meal, they jump.They do spin a silky “dragline” as they jump, for safety. Their jumps may carry them several times up to 40 times their body length (which is admittedly not very long), all without benefit of big, burly leg muscles. The theory is that the spider enjoys some sort of hydraulic assist—contracting the muscles in the front part of its body raises the blood pressure and causes the legs to straighten rapidly. One reference likened it to squeezing the bulb of the toy frog and watching its rubber legs straighten. The BugLady has concluded that it’s magic, like the click beetle’s ability to right itself.

Notable JSs:

- For those of us who were taught that spiders are carnivores—period—the JS holds more surprises. Yes, they spot, track, pounce on, and bite their prey—any invertebrate they can catch, including other spiders. But some JSs are omnivores, feeding on nectar and pollen as well as on the pollinators, and one species is primarily vegetarian.

- Several species of JS are ant-mimics, looking like, behaving like, and eating ants. They “infiltrate” a group of ants and go so far as to imitate the ants’ greeting rituals before scarfing their prey.

The sex life of the JS can be summarized with one word—risky. The colorful males dance and flash their colors to compete for and to pacify the females, who are larger and always looking for prey. In a ritualized dance the male will show off his various fringes, colors, and iridescences. He will wave, zig-zag, vibrate, buzz, and sidle. If a female is not in the mood, she may watch the show before eating him. If they do exchange bodily fluids, he must exit quickly. A female JS may stay and protect the eggs she encloses within a silken shelter. The young hatch looking like mini jumping spiders and simply grow, through a series of molts.

Like other spiders—and most wildlife—JSs will not bother people unless people bother them—for “bother” read “corner,” “poke,” or “handle.” That’s why we call them wildlife. Their bites are classified as itchy and painful, with the potential for several days of redness and swelling, especially in people who are allergic to spider bites.

The California Poison Action Line contributes this addendum (the BugLady did not make this up):

Spiders do not attack in herds. Spiders do not lay in wait and attack people. Spiders do not lift the covers at night and crawl into bed to bite people as they are sleeping. Some spiders can jump but they are not intentionally jumping at humans to attack them. A spider generally bites a human because it was scared and bites to defend itself. Spiders generally prefer to live in undisturbed areas such as corners of the house or the eaves or in the garden where they can catch insects in peace.

The BugLady