Richard Avedon once won a teen poetry contest. It’s a tiny factoid that bobs like a little buoy in the great sea of accolades that has surrounded his body of work as a photographer—one he began creating in earnest at Harper’s Bazaar in the waning days of the Second World War and continued to restlessly reshape and reimagine until his death in 2004 at the age of 81. Avedon’s winning entry in the 1941 Scholastic Art & Writing competition was a poem called “Wanderlust,” in which the narrator appears eager to leave home in search of new people, places, and experiences despite those who caution him to take a more conventional path. It begins with the couplet “You must not think because my glance is quick / To shift from this to that, from here to there,” and concludes, “I know my drifting will not prove a loss, / For mine is a rolling stone that has gathered moss.”

A sampling of what Avedon found as he ventured out into the world with his camera will be on view in “Avedon 100,” opening on May 4 at the West 21st Street outpost of Gagosian gallery in New York. The exhibition, to mark what would have been Avedon's 100th birthday, brings together close to 150 images drawn from every corner of his six-decade career as a fashion photographer and portraitist and selected by the likes of Hilton Als, Naomi Campbell, Thelma Golden, Elton John, Tyler Mitchell, and Kate Moss. These include examples of his monumental work for Bazaar between 1944 and 1965—among them, perhaps his most monumental, a 1955 image now known as Dovima With Elephants, of the model Dovima, a forerunner to the “super” version of the 1980s and ’90s, regally swathed in a Dior gown and flanked by a pair of pachyderms at the Cirque d’Hiver in Paris. The show will also be accompanied by a book, Avedon 100 (Rizzoli), which will include additional behind-the-scenes documentary images, a series of new essays, and a foreword by Larry Gagosian, who first exhibited Avedon in 1976.

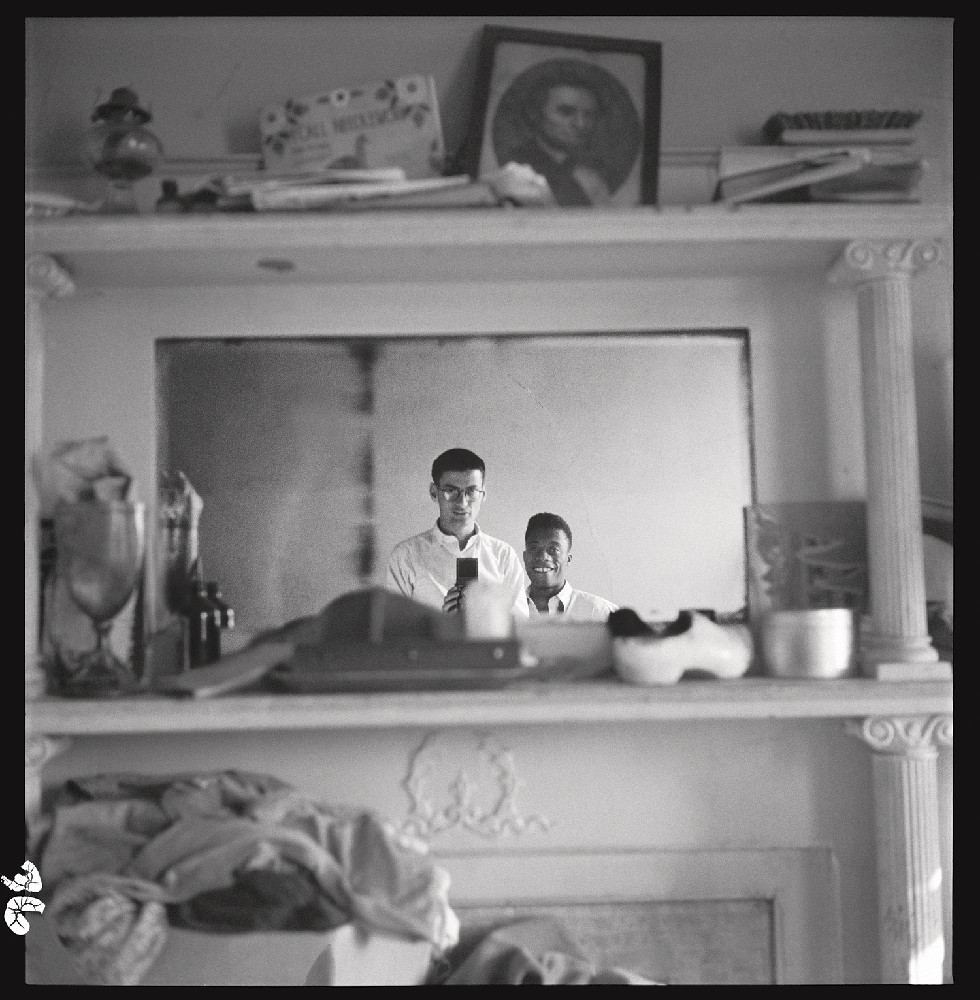

“Avedon 100” also includes a pair of self-portraits of Avedon with another teen poet he’d befriended while attending DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx: the writer James Baldwin. Avedon, whom everyone called Dick, and Baldwin, then known as Jimmy, served as coeditors on DeWitt Clinton’s literary journal, Magpie.

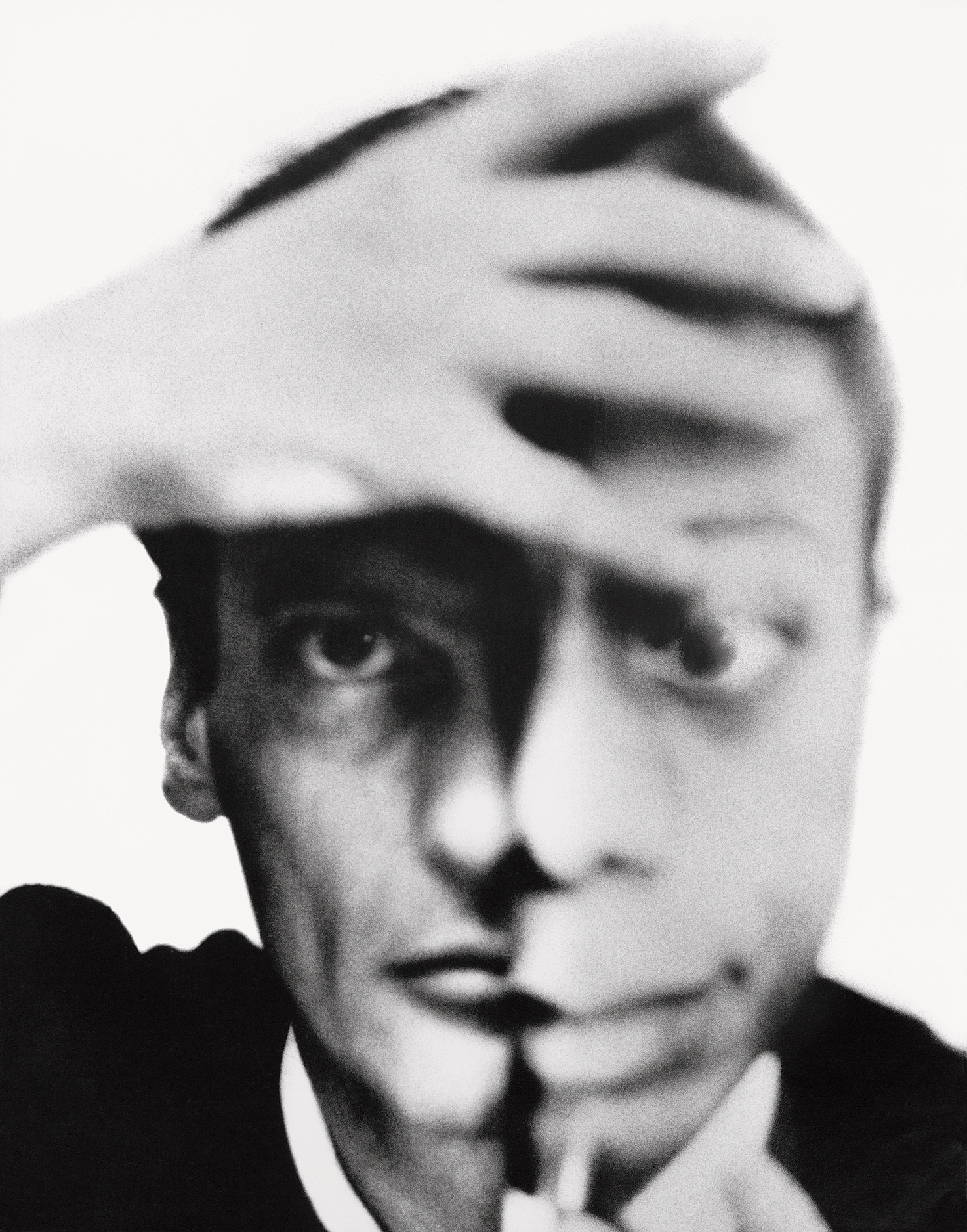

The images, taken almost two decades apart, roughly bookend Avedon's time at Bazaar. The older one is a mirror selfie of the duo shot by Avedon in 1946, when they were both in their early 20s and still budding. The later one, which appeared in Bazaar’s November 1964 issue, is a photograph of Avedon holding a cropped picture of Baldwin’s visage over his own. By then, they’d both achieved an entrenching kind of fame: Dick, having served as the inspiration for the Fred Astaire character in the 1957 Stanley Donen musical Funny Face; Jimmy, having emerged as one of the most vital literary voices of the postwar period and an intellectual force in the civil-rights movement.

Avedon was white and Jewish, Baldwin Black and gay, but they quickly bonded over their love of art. They found sanctuary with a group of other literary aspirants in the Magpie offices, housed (quite literally) in a tower atop DeWitt Clinton, where their classmates included the playwright and screenwriter Paddy Chayefsky, the essayist and author Emile Capouya, and Baldwin’s future editor Sol Stein.

Avedon's father, Jack, once owned a Fifth Avenue department store but lost it after the stock-market crash of 1929. The Avedons then moved from their house on Long Island to a modest three-room apartment on East 98th Street; Dick slept in the dining alcove. His mother, Anna, who had wanted to be an artist, shepherded Dick and his sister, Louise, to museums and theaters and filled their home with books and magazines. Louise would become one of Dick’s first subjects after he picked up his father’s camera at the age of nine. The Avedons were a tight-knit group; still, to maintain appearances, they often took family photos with other people’s cars and dogs.

Baldwin was raised in Harlem, the eldest of nine children. The Baldwins lived in a succession of tenements, where Jimmy was often left to care for his brothers and sisters. He never knew his biological father. Jimmy’s mother, Emma, cleaned houses. His stepfather, David Baldwin, was a preacher; for a period in his teens, Jimmy was one too. But Jimmy soon rejected the elder Baldwin’s religious fervor as he watched David, who often lost his temper, struggle with racism, money, and his own mental health.

After leaving Dewitt Clinton, Avedon and Baldwin hatched a plan to create a book of photographs and text that they referred to as Harlem Doorways. The project, though, never came to fruition, and they eventually lost touch.

Avedon, who had begun to channel more of his energy in photography, arrived at Bazaar in 1944 as a dewy 21-year-old fresh off a stint in the U.S. Maritime Service in Sheepshead Bay, Brooklyn, where he had bided his time shooting events and shipwrecks. After he was discharged, he enrolled in a class at the New School taught by Bazaar’s vaunted art director Alexey Brodovitch, with intent of capturing Brodovitch’s attention so he could shoot for Bazaar. Brodovitch, after much cajoling, finally agreed to give Avedon an assignment for the magazine. Avedon, the story goes, shot some fashion images on his own to show Brodovitch, but Brodovitch was quickly dismissive of those pictures. Instead, Brodovitch pointed to a portrait of a set of twin brothers that Avedon had taken while in the Merchant Marine, where one appeared crisp and the other out of focus. Brodovitch implored Avedon to apply that kind of experimental approach to fashion photography, which Avedon did dutifully over the next 21 years.

There was a light, inventive touch to Avedon’s fashion work for Bazaar, like his 1957 image of Carmen Dell’Orefice suspended in midair as she skipped over a puddle or his 1962 story with Suzy Parker and Mike Nichols as an Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton–esque couple on the run in Europe from the paparazzi. But what Avedon brought to fashion photography was a kind of modernist sensibility: that there was some truth to be gleaned from how we express (or try to suppress) our deepest hopes, desires, and even delusions—the ways we “perform” in life.

It’s not a coincidence that one of Avedon’s favorite subjects during his time at Bazaar was Dovima, a.k.a Dorothy Virginia Margaret Juba from Queens, who had ascended to the most rarified sanctums of fashion after reinventing herself by taking the name of an imaginary friend she’d concocted as a child. In 1986, a reporter for a Florida newspaper found her working as a hostess in a pizza parlor in Fort Lauderdale, where she’d moved with her third husband to be closer to her parents, who had retired there. “It always seemed like I was watching a movie,” Dovima recalled of her days at the apex of the industry. “And I’m in the movie. Only it really isn’t me.”

Avedon and Baldwin reconnected in 1963 when Avedon was asked to photograph Baldwin for Bazaar. By then, Baldwin was already a literary star following the success of Go Tell the Mountain (1953) and Giovanni’s Room (1956). But the publication that year of Baldwin’s nonfiction book The Fire Next Time, a searing examination of the profound depth and impact of racism in the U.S., would propel him to an entirely new level of notoriety, landing him on the cover of Time.

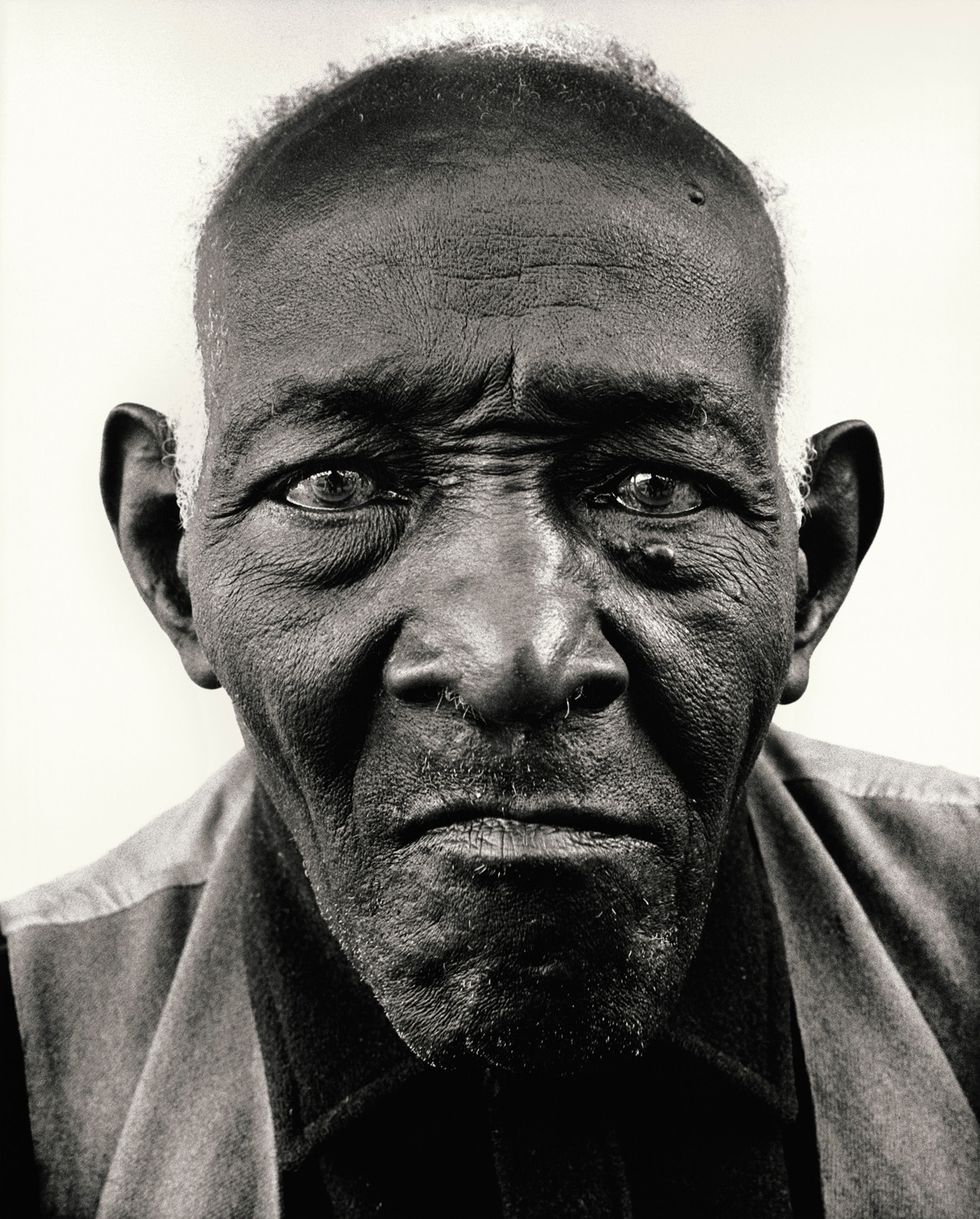

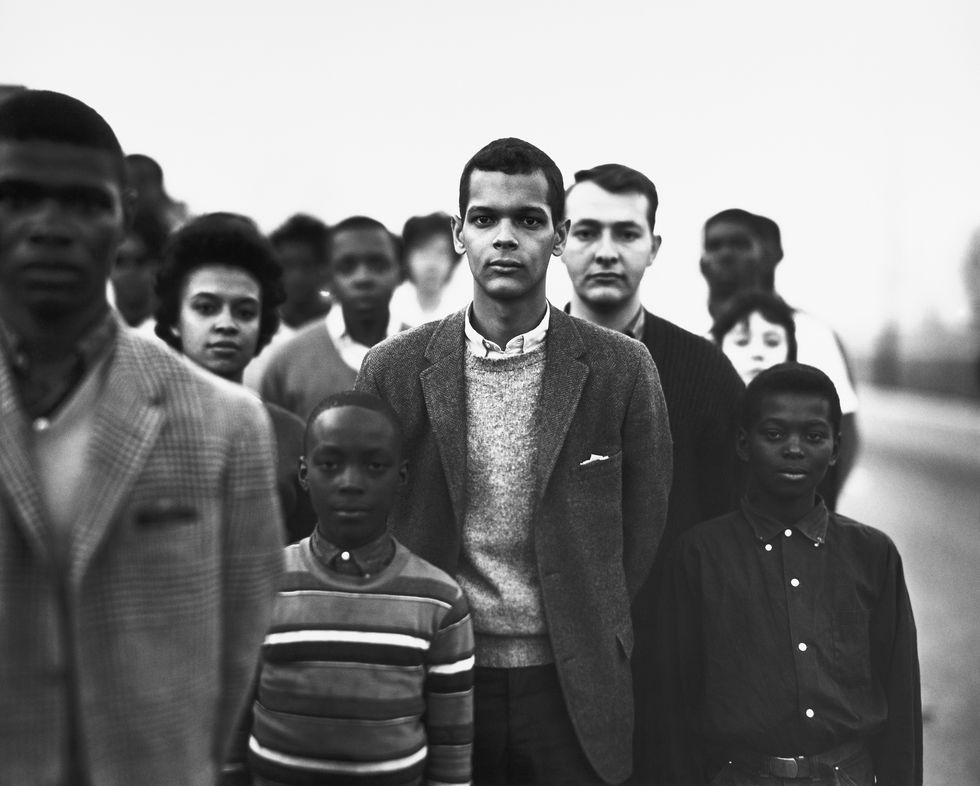

The reunion led to their collaboration on 1964’s Nothing Personal, a volume of images by Avedon, with text by Baldwin, that explored the nature of American identity at a moment not unlike our current one, when the country was roiling, divided, and tearing itself apart. Published just months after the passing of the Civil Rights Act, Nothing Personal included portraits of Marilyn Monroe, Allen Ginsberg, Julian Bond, Marian Anderson, and William Casby, one of the last people alive to have been born into slavery, alongside images of segregationists, members of the American Nazi Party, and the Daughters of the American Revolution. Baldwin had spent the preceding years in quasi-self-imposed exile, having decamped in 1948 for Paris to escape what he once described as the “social terror” of the discrimination and homophobia he encountered growing up in America, a place where the overarching vision of liberty and prosperity seemed to have little room for him in it.

At one point during the making of Nothing Personal, Avedon, who had been furiously taking pictures, went to Puerto Rico to meet up with Baldwin, who had not yet written a word of text for the book. They later reconvened in Paris, where Dick whisked Jimmy away to the home of a physician friend. For two days, Jimmy holed up in a guest room, knocking out what would become the first section of Nothing Personal—a parabolic riff on the warped depictions of American life that he saw in the ads on TV—while Dick slept on a couch. “I know the myth tells us that heroes came, looking for freedom; just as the myth tells us that America is full of smiling people,” Baldwin wrote. “But the relevant truth is that the country was settled by a desperate, divided, and rapacious horde of people who were determined to forget their pasts.”

It was with Nothing Personal that Avedon began to refine a certain style of portraiture: His subjects were often captured against minimal white backgrounds with blown-out lighting—a device, as Avedon once described it, that allowed them to be “symbolic of themselves.” In the Merchant Marine, one of Avedon’s assignments was to photograph mugshots for ID cards. There are shades of that practice in his portraits: in their spareness and directness; in the way people appear isolated, in controlled environments, as the summation of their physicalities, experiences, and ambitions.

In the years that followed, Avedon’s work often got bigger in every sense of the word: the mural-size portraits he shot in the late 1960s of the denizens of Andy Warhol’s Factory and the Chicago Seven, the expansive visual essays on the post-Watergate U.S. political establishment (1976’s “The Family”) and the vast terrain of the nation itself (“In the American West,” 1979–1984)—all represented in “Avedon 100.”

Like every teen poet, Avedon yearned to be taken seriously. But like Baldwin, he also understood the complicated relationship people have with their own mythology. To an extent, Avedon saw America—and the fashion world—as places people could both lose and find themselves, for better or for worse. At the time of his death, he was in Texas working on a story about the fractured mess the country had become in the aftermath of the disputed 2000 presidential contest between George W. Bush and Al Gore and the tragedy, fear, anger, and national soul-searching in the wake of 9/11, with contentious wars raging in Afghanistan and Iraq. The project was provisionally titled “Democracy,” and he had no doubt set off in search of it.

A version of this story appeared in the May 2023 issue of Harper's Bazaar.

Stephen Mooallem is editor at large at Harper’s Bazaar. He is the former editor in chief of Interview and The Village Voice.