Scatella

Summary 4

Scatella is a genus of shore flies in the family Ephydridae. There are at least 140 described species in Scatella.

comprehensive description 5

Scatella (Scatella) favillacea Loew

Scatella favilacea Loew, 1862:170—Wirth, 1968:25 [Neotropical catalog].

SPECIMENS EXAMINED.—BELIZE. Stann Creek District: Man of War Cay, Nov 1987, W.N. and D. Mathis (1).

DISTRIBUTION.—Nearctic: Canada (ON, SK, QB), USA (FL, IA, MA, MD, NJ, OH, TX, VA). Neotropical: Belize, Costa Rica, Ecuador.

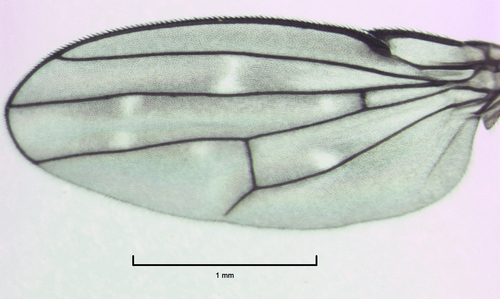

DIAGNOSIS.—This species is closely related to S. paludum (Meigen) but is distinguished from it and other congeners by the following combination of characters: mesofrons shiny with metallic luster, bare of microtomentum, rounded laterally and broadly, reaching to anterior margin; gena high, over one-half eye height; face, lateral margins of mesonotum, and pleurae silvery gray; posterior notopleural seta inserted at level conspicuously above anterior seta; wing hyaline, lacking prominent spots.

Discussion and Summary of Shore-Fly Diversity and Island Zoogeography

Among terrestrial organisms that occur on Belizean cays, the Ephydridae, with 56 known species, exhibit exceptional diversity (Table 1). Based on data presently available, no other family of plants or animals approaches this degree of species richness, although few groups, insects in particular, have been collected as thoroughly as the Ephydridae. Other families that have been well sampled for comparative purposes are ants (Formicidae), with 34 species (Lynch, pers. comm., 1993), and long-horned beetles (Cerambycidae), with 20 species (Chemsak, 1983; Chemsak and Feller, 1988; Feller, pers. comm., 1993).

The diversity of species, as measured within the higher classification of shore flies (Table 1), is greatly skewed toward the subfamily Gymnomyzinae, with 38 of 56 species or two-thirds of the known shore-fly fauna on the Belizean cays. The species of Gymnomyzinae that occur on the cays are distributed among nine tribes and 21 genera. The remaining three subfamilies and their included species

The essentially harmonic shore-fly fauna of the Belizean cays was also expected, especially when distance from the mainland and principal source pool is considered. The cays are relatively close to the mainland and are more typical of continental islands. Most of the cays we sampled are associated with the barrier reef and are at most approximately 18 km from the mainland. In time, many if not most shore-fly species could possibly bridge that gap as aerial plankton (Glick, 1939; Guilmette et al., 1970; Gressitt, 1974). Double that distance, however, such as the distance from the mainland to the cays of Glover's Reef, apparently does pose a more significant barrier. Of the 12 species found on Glover's Reef (Table 5), all but three (Paraglenanthe bahamensis, Paratissa neotropica, and Paralimna fellerae) are among the most widespread species occurring on Belizean cays. Among species that occur on one-half or more of the cays (Table 6), over one-half (eight of 13 species) are found on Glover's Reef (Table 5). This probably indicates differential vagility among these species, at least for distances beyond 30 km from the mainland or over 15 km from the nearest barrier reef cays.

The proximity of the barrier-reef cays to the mainland, however, has almost assuredly been a contributing factor to the exceptional diversity of shore flies on these islands. Almost without exception, the species of shore flies known from the Belizean cays also occur on the nearby mainland, and it is likely that most if not all species are introductions to the cays from source pools on the mainland through various means of introduction and dispersal. As the species occurring on the cays are macropterous and presumably quite vagile, most, perhaps all, probably arrived on the cays through either active or passive mechanisms (i.e., their own powers of flight combined with prevailing winds) or a combination of them. Those species that are specifically associated with certain plants, such as Ceropsilopa coquilletti on Suaeda linearis, may have arrived on the cays with the introduction of their host plants.

Although shore flies are unusually diverse on the cays, additional species undoubtedly await discovery. Only a few cays within the Stann Creek District were sampled (see section on “Islands and Habitats”), and these represent a small fraction of the total number of Belizean cays. Moreover, my experience from conducting field work on Belizean cays indicates that other species will be discovered. For example, each of the first few field trips resulted in several additional species, especially when sampling took place during different seasons. Even though fewer additional species were found in recent years, only two in 1989 and none in 1990, others will almost certainly be discovered, perhaps as introductions.

Introductions are likely to increase as commerce and trade expand in the western Caribbean. In 1989, for example, Hecamede brasiliensis was discovered in abundance on several cays, and each of these cays had been intensively collected for the previous five years without any indication of this species. Its rather sudden occurrence and apparent establishment are likely to have resulted from an introduction. This same species was just recently found on the Galápagos Islands, and its occurrence there is also adventive (Mathis, 1995b).

A second species that was probably introduced is Discocerina mera, which occurs throughout the study area. This species was first collected in 1985 and has been found on all subsequent field trips. The records of its occurrence in Belize, however, are the first in the Western Hemisphere (Zatwarnicki, 1991). Elsewhere the species occurs throughout the Australasian and southern Oceanian regions and into the Oriental (Thailand to the Ryukyu Islands) and Palearctic (Japan) regions.

Earlier, Cresson (1946a: 152) suggested that a third species, Clasiopella uncinata, is also an introduction in the Caribbean region and in Florida. Cresson's suggestion was based on several interceptions of this species on airplanes that were sampled during World War II (Cresson, 1945, 1946a, 1946b). The airplanes were from such widespread sites as Midway Island, the Caribbean, and Kenya.

The fourth species that was likely to have been introduced is Placopsidella cynocephala, which was found on Half Moon Cay (Lighthouse Reef). Prior to its discovery on Belizean Cays, this species was known only from the Oriental and Australasian/Oceanian regions. This is the second species of Placopsidella that is apparently adventive to the New World. Previously P. grandis was reported from Panama and coastal Maryland and Virginia (Mathis, 1986b, 1988).

Shore-fly species richness on the Belizean cays results from complex biotic and abiotic interactions over an extended period of time, perhaps millennia. Some of the factors contributing to the complexity were discussed above, i.e., habitat availability, tolerance or intolerance to saline habitats, climatic factors, distance from possible source pools, and introductions through commerce.

Shore flies, as the vernacular name for the Ephydridae suggests, are primarily associated with shorelines in aquatic and to a lesser degree in coastal marine ecosystems. These habitats, coastal marine ones in particular, are diverse on the cays. Although terrestrial habitats on the cays are much more restricted than those on the mainland, several are quite suitable for shore flies. Habitats where greatest numbers of species were collected were described earlier in the section dealing with “Island and Habitat Descriptions.”

On the basis of diversity per island, Wee Wee Cay and Twin Cays have by far the greatest richness (Table 4). Even with a bias due to the more intensive sampling on Twin Cays, there is probably greater diversity there because of the variety of habitats and greater size of the islands. On Wee Wee Cay, however, which is a small cay that was not sampled as intensively, the marked diversity in shore flies is attributable to the freshwater habitat, even though it may be ephemeral. Of the 33 species found on Wee Wee Cay, nine were exclusive within the cays to that island and are primarily freshwater species.

Another aspect of shore-fly biogeography on Belizean cays is the occurrence of a particular species on different islands (Table 4). Sorting species by this criteria indicates that 21 of 56 species (38%) occur on a single island and that only Discocerina mera was found on each of the 13 islands (Table 6). Moreover, only eight species (14%) are known to occur on one-half or more of the cays that were sampled (Table 6).

A further consideration that contributes to the richness of shore flies on the cays is the life-style strategy of many shore flies. In addition to being diverse, most of the habitats that are exploited are comparatively ephemeral, especially the freshwater habitat on Wee Wee Cay. The shore flies using these habitats are typically r-strategists, i.e., they are able to quickly find and exploit a short-lived microhabitat and demonstrate minimal behavior in dealing with each other and/or the habitat. R-strategists usually emphasize high fecundity and quick and effective dispersal mechanisms. Given the rapid change in habitats that frequently occurs on the cays, mostly due to climatic factors, shore flies ought to be well accommodated. Their life style as r-stragetists, coupled with a tolerance for saline conditions, which significantly reduces competition, are at least partial explanations for their occurrence and marked diversity on Belizean cays.

Eighteen percent of the fauna treated herein (10 of 56 species) represents undescribed species that were collected as part of field work for this study and described recently or in this paper. Endernism, however, should be considered an uncharacteristic phenomenon on the cays, with most or perhaps all of the new taxa also occurring on the nearby mainland or elsewhere in the Caribbean. Why endemism is a remote possibility seems fairly evident, although lacking empirical confirmation. First, as was discussed earlier, the cays are close to the mainland, and the relatively narrow gap could easily be spanned by shore flies, most likely as aerial plankton. Second, the cays are comparatively young on a geologic time scale (7,000 bp; Shinn et al., 1982) with insufficient time for isolation and localized speciation. Third, the cays are small and low lying, with a relatively limited niche capacity and topography. Fourth, the cays are subject to rapid, sometimes catastrophic physiographic change. Carrie Bow Cay, to cite just one example, lost approximately 30% of its surface area during a single hurricane in 1974 (Hurricane Fifi; Rützler and Ferraris, 1982). For these reasons, endemism was neither foreseen nor found, and its plausibility in the future remains untenable.

Species Number of islands

1. Ptilomyia lobiochaeta 5

2. Ptilomyia parva 6

3. Allotrichoma abdominale 11

4. Diphuia nasalis 7

5. Paraglenanthe bahamensis 3

6. Discocerina flavipes 8

7. Discocerina mera 13

8. Polytrichophora conciliata 9

9. Ceropsilopa coquilletti 6

10. Paratissa neotropica 3

11. Paralimna fellerae 3

12. Scatella obscura 7

Species Number of islands

1. Discocerina mera 13

2. Allotrichoma abdominale 11

3. Polytrichophora conciliata 9

4. Paratissa semilutea 8

5. Glenanthe ruetzleri 8

6. Discocerina flavipes 8

7. Diphuia nasalis 7

8. Scatella obscura 7

9. Mosillus stegmaieri 6

10. Ptilomyia lobiochaeta 6

11. Ptilomyia parva 6

12. Ceropsilopa coquilletti 6

13. Paralimna obscura 6

The proximity of the cays to the mainland, the availability of suitable habitats, and the vagility of most shore flies are probably sufficient to account for most species on the cays. Not all of the species we found on the cays, however, may represent established breeding populations. Because most of the samples from the cays are based on adults with little work on the immature stages, the criteria for determining whether a sample represents a breeding population are mostly drawn from inferences, such as abundance of a species, occurrence on more than one cay, or maintenance of a population from season to season or year to year. Applying these criteria, nine of 56 species (Gastrops niger, Discocerina nitida, Hydrochasma faciale, Hydrochasma species, Hydrellia cavator, Notiphila erythrocera, Zeros obscurus, Hyadina flavipes, and Scatella favillacea) or 16% may possibly represent nonbreeding populations on the cays. For most of these species, we collected single specimens, and it would be reasonable to assume that they are occasional migrants to the cays. I have deliberately used noncommittal language in this section, however, as sampling error is undoubtedly a major contributing factor.

Among terrestrial animals, few have demonstrated the adaptive ability to exploit saline habitats like the ephydrids. Moreover, this family, more than other acalyptrate groups of Diptera, has adapted to numerous and often remarkably diverse habitats, prompting Oldroyd (1964:188) to comment:

Clearly, then, Ephydridae are nothing if not versatile…. Evidently we are seeing in the Ephydridae a family of flies in the full flower of its evolution, and as such they offer attractive material for study, not only to the dipterist, but also to the student of insect physiology and behaviour.

Sources and Credits

- (c) Steve Kerr, some rights reserved (CC BY), uploaded by Steve Kerr

- (c) Nikolai Vladimirov, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), uploaded by Nikolai Vladimirov

- (c) Stephen Thorpe, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC), uploaded by Stephen Thorpe

- (c) Wikipedia, some rights reserved (CC BY-SA), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scatella

- Adapted by monkeyjodey from a work by (c) Unknown, some rights reserved (CC BY-NC-SA), http://eol.org/data_objects/27273914