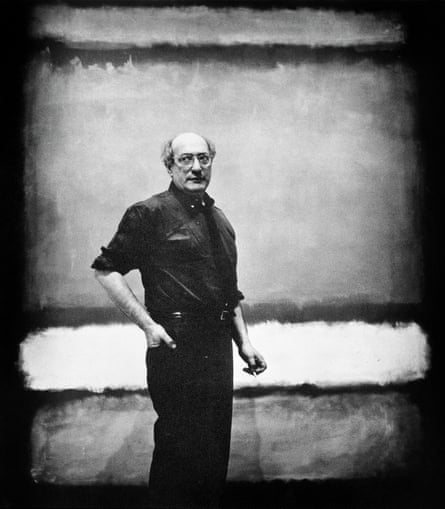

Mark Rothko’s final decade is typically thought of as a journey into darkness, when the American abstract expressionist’s furnace-bright hues of the 1950s all but vanished. His canvases, huge as stage curtains, grew doomy with maroons, browns and blacks. The great smouldering Seagram murals, commissioned for a corporate dining room but withdrawn by the artist and donated to galleries, were followed by the Rothko Chapel in Houston: this fusion of art, spiritual architecture and a clear-eyed confrontation of death was his crowning achievement, and what pushed him to the limit. By 1968, after years of heavy drinking, Rothko’s health was in ruins. Marital breakdown was followed by suicide in 1970.

Quick GuideSaturday magazine

Show

This article comes from Saturday, the new print magazine from the Guardian which combines the best features, culture, lifestyle and travel writing in one beautiful package. Available now in the UK and ROI.

But a new exhibition of little-known paintings from the late 1960s looks to expand our understanding of his art and even counter that bleak narrative. Realised in a fresh medium, acrylic on paper, the works in Mark Rothko 1968: Clearing Away were prompted by a doctor’s warning: after an aneurysm, Rothko was ordered to quit booze, smoking and painting big oils. He managed the last. The show explores what Christopher Rothko, his son and overseer of the Rothko estate, describes as “the necessity that he change the scale of his thinking, but also a fresh chapter”.

These late experiments include a return to a brighter palette, as well as furthering the innovations with texture that he had been developing in his public commissions. Even when the painting was at its darkest, it was never one-note, Christopher says: “He’ll create a painting that looks like it’s a step from the abyss, and yet he’ll nearly always give you something that creates light.”

Christopher was five when Rothko began using acrylics. He recalls how his dad, known for being particular when it came to gallery installations, would bring work home and put it up apparently at random. In one of 20th-century art’s great scandals, the pieces that surrounded the artist’s son as a young child disappeared from his life when his father died: his estate executors sold Rothko’s work at less than market value to London’s Marlborough Fine Art, thereby defrauding the family. Christopher’s older sister Kate was compelled to fight a lengthy court battle against the executors and the gallery; although many considered the action doomed, she was successful and they were ordered to pay the estate millions. Christopher was 12 when the case ended. “Miraculously,” he says, “we prevailed.”

Many of the works in Clearing Away come from Marlborough’s ill-gotten haul, including the very first one, “a little green and blue painting” that Christopher put up in his first apartment after he graduated from college.

“I was thrilled to come home from work each day and see this painting there,” he says. “Some sort of order to the world had been restored.”

These late paintings are also a reminder that, like his art, Rothko’s final years had moments of luminous energy.

“He was juggling tremendous internal and external difficulties and yet painting more than he ever had and not stagnating or winding down,” Christopher says. “He was continuing to work in a life-affirming way.”

Mark Rothko 1968: Clearing Away is at Pace Gallery, London, 8 October to 13 November.

Christopher Rothko on his father’s late works

[Main image, above] “This is most reminiscent of his earlier works. The white is bright, the yellow is brilliant. I’m cautious to say the paintings reflect mood. Rather, it’s that even though he’s in terrible health and is often quite depressed, painting is ‘everything’ for him. He’s very open to what it brings out in him.”

“At first glance the work is dark and there’s not much to see there. All it takes is a tiny blue band to let you see that this [above] is not a gloomy painting by any means. The more you look at the blue, you realise how soft the blacks are. It’s a serious painting, but with passionate feeling.”

“This [above] has the feel of some of my father’s canvases, in how these very dynamic rectangles are interacting with their background. He is known for his use of red and it’s one of the few red paintings you see from these works on paper. It also shows the power of white and its tremendous impact in his painting.”

“Because the Rothko estate was defrauded, for years my sister and I had no works to hang. This [above] was the first painting I hung when the litigation was finally settled. Justice had been served and we had a new connection to our father. It always brings back that happy glow.”