Little House and the Art of Hiding Your Feelings

Laura Ingalls Wilder’s popular book series championed emotional restraint—an approach I’ve come to both question and appreciate in adulthood.

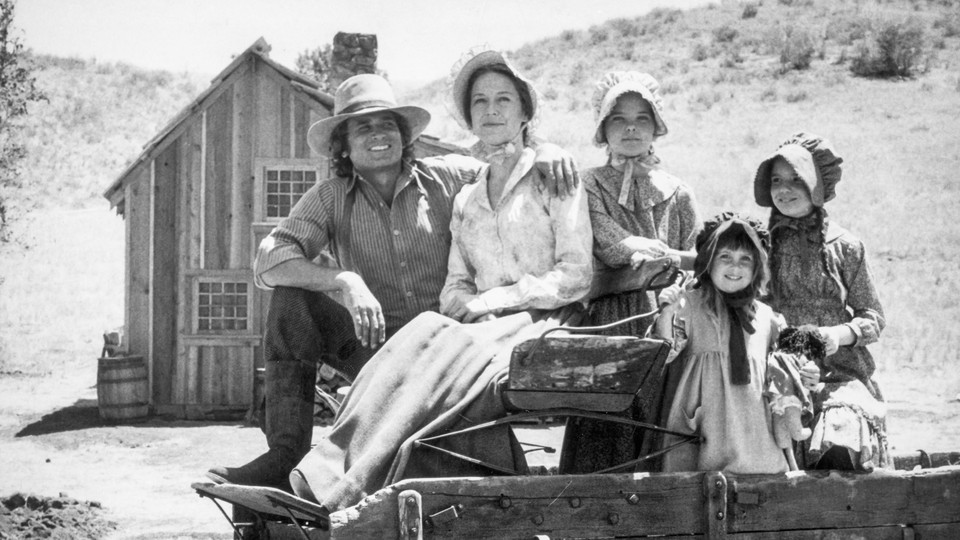

Laura Ingalls Wilder’s semi-autobiographical series Little House on the Prairie tells the simple but sprawling story of a young pioneer girl and her family as they journey across the American frontier in the 1880s. First published during the Great Depression, the novels have since been fairly criticized for their depiction of Native Americans, but this troubling aspect hasn’t diminished their popularity (they’re beloved by the feminist writer Roxane Gay and the former Alaska governor Sarah Palin alike). Today, the books disturb me as much as they move me—but as a kid, I longed for someone to develop the technology to print Little House on the backs of my eyelids, so that no matter what I was doing I could always be with Laura, racing ponies across the prairie or making maple sugar candy in the Big Woods.

I read the novels almost continuously from ages 6 to 10. I put on a bonnet to play Little House and wore a nightcap to bed so I could sleep Little House. I’m not sure where, exactly, a book ends and a reader begins, but I know that as a kid I did my best to make that dividing line very fuzzy. Little House helped me to hold myself back from the 1980s of my childhood, and allowed at least a small part of me to grow up in the 1880s—or at least the 1880s as remembered in the 1930s. This may be why I sometimes feel a little bit “out of time,” if not out of place, in 2016. For one thing, I’m convinced that Little House has prevented me from becoming an emotionally on-trend woman who “leans in” and “lives her personal truth.”

Instead of following Oprah or Sheryl Sandberg, I have—for better and worse—heeded the stoic wisdom of Wilder, who writes in Little Town on the Prairie that “grown-up people must never let feelings be shown by voice or manner.” In other words: I’m passive-aggressive, I secretly pursue my own agenda, and—the greatest of self-care sins—I hide my feelings. As an adult, I’m baffled by the stars of reality dating shows like The Bachelor, less by their appetite for public scrutiny than by their fluency in an emotional vernacular that feels both evangelical and alien. Over candlelit dinners, contestants confess their love and relate traumatic stories in order to prove they’re “ready to open up and be vulnerable.” While Little House and The Bachelor are forms of reality-based fiction, autobiographical works like the former are usually associated with self-expression. But across eight volumes and hundreds of pages, Wilder and her characters repeatedly tout the dangers of sharing your feelings. Over the years, I’ve come to accept this sentiment’s many pitfalls, while trying to better understand the historical and cultural value it held for pioneers like the Ingalls family.

Wilder expects not only her characters, but also her readers, to understand that displays of emotion are inappropriate. In Little House on the Prairie, when the girls must bid a final farewell to their friend Mr. Edwards, a six-year-old Laura accidentally shows emotion—or, as Wilder puts it, she “forgets to be polite.” Laura breaks prairie protocol by exclaiming passionately: “‘Oh Mr. Edwards, I wish you wouldn’t go away!’” Later, when her younger sister Carrie dares to hope that Laura’s boyfriend Almanzo will survive a mission into the frozen hellscape of The Long Winter, the more-mature Laura stays quiet because giving voice to her feelings “would not make any difference.” Throughout the series, Laura understands that part of growing up means learning to keep “a stiff upper lip.”

It’s a lesson Laura carries with her into the last book of the series, These Happy Golden Years. Her emotional restraint—and maturation—culminates in her engagement to Almanzo, which is accomplished without discussion of feelings. Mid-buggy ride, Almanzo asks Laura if she would “like an engagement ring.” She replies, “That would depend on who offered it to me.” He specifies: Would she like an engagement ring from him? It would depend, she tells him coyly, on the ring. When Almanzo returns with a ring, Laura approves it, saying only, “I think ... I would like to have it” (ellipses Wilder’s).

The sentiment in Laura’s acceptance is contained entirely in the ellipses—in what the Bachelorette star Ashley Hebert called, “the dot-dot-dot,” after a departing contestant left open the possibility of a future relationship with her by mysteriously saying, “Who knows ...” In the universe of the Bachelorette, any emotional omission, any vagueness of feeling, is ferreted out immediately. Log-cabin-style emotional withholding is not tolerated in the Bachelor Mansion, where the producers are quick to arrange for a confrontation that might devolve into a profession of love, a profusion of tears, or a dip in the hot tub. Of course, there are no ardent love scenes—and no hot tubs—in Little House.

I grew up 45 miles from Wilder’s birthplace in Pepin, Wisconsin, a part of the world where people spend their whole lives in the “dot-dot-dot.” We try not to bother others with our feelings, and we leave a lot unsaid. In one (perhaps extreme) example: A family friend, an elderly woman, woke up at 3 a.m. with chest pains. She thought about calling 9-1-1, but decided not to. If the ambulance came, the siren might wake the neighbors. She considered calling her kids, but she didn’t want to worry them. So she drove herself to the emergency room. When she arrived, she opted not to take one of the parking spots close to the entrance, because someone else might need it. For so many of us in Wilder country, emergencies happen to other people.

Woven into this extreme reluctance to burden others is an emphasis on self-sufficiency—yet another hallmark of the pioneer spirit Wilder advocates in her books. Always critical of Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the New Deal, she gave a 1937 speech in which she recalled a frontier where “neither [her family] nor their neighbors begged for help. No other person, nor the government, owed them a living ... we need today courage, self reliance and integrity.” Good humor and cheerfulness spur that all-important courage, Wilder argued. It’s how families like hers boosted their morale and avoided succumbing to the despair of prairie life, as Mrs. Brewster does one winter night, screaming at her husband, seizing a butcher knife, and threatening to kill herself if he won’t take her back East.

In These Happy Golden Years, Wilder gives readers a perfect contrast between Laura—who adheres to the cardinal value of emotional repression—and the sulky, gravy-stained Mrs. Brewster, who Laura stays with one winter while teaching at a prairie school. At first, it hurts Laura’s feelings when Mrs. Brewster doesn’t return her “good morning.” But Laura learns a valuable lesson from Mrs. Brewster’s sullenness: It’s the Ingalls family’s cheerful exchange of greetings that makes the morning good. By quashing feelings and swapping smiles, the Ingalls family made frontier hardship endurable.

Years after reading those books, I moved to Madrid to teach school, just as Laura moved far from her family’s home on the frontier. I discovered that living far away can give you perspective on the unique emotional economy of your home. I couldn’t seem to make anything work in Madrid. I spoke Spanish, but no one understood me, and I never got what I wanted. I think this was because I spoke Spanish in ellipses—that is, I tried to leave things unsaid, the way I would in English. People didn’t give me things, because I wouldn’t dare ask.

Carrying around the belief that asking for help somehow amounts to weakness hasn’t always served me well, especially in other cultural contexts. When I was moving back to the U.S., an issue with the airline delayed me for several days. Spanish airport-security agents, who had watched me repeatedly and politely fail to get a seat on a flight to the States, finally took me aside and explained that I needed to go up to the Iberia desk, take hold of the counter, and yell and cry without stopping until I got what I wanted. I was shocked. I couldn’t do it, I told them. So they rallied two other passengers to stand behind me and support me while I became Mrs. Brewster (minus the knife). Within a few hours, I flew home. I’m still grateful to those strangers who boosted my morale, not with their cheerfulness but with their indignation.

There are more insidious downsides to Wilder’s approach. The Minnesota-based activist writing collective Of Nine Minds criticizes Little House on the Prairie culture, linking emotional repression to political oppression. The group points out that the stakes of expressing feelings have always been higher for people of color, and that a culture of “niceness” only exacerbates this problem. Further, it’s hard to advocate for yourself when good people aren’t supposed to ask directly for what they want; it’s hard to bring attention to serious grievances when you’re not supposed to express negative feelings. Indeed, how are we supposed to make the world a better place when we can’t complain?

At the same time, I’m reluctant to travel too far from Little House. I still think there is some modern value in the kind of emotional socialism Wilder proposes, where everyone sacrifices personal gratification for the greater good. I moved back to Wisconsin last year, after a decade living away from the Midwest. I notice that when I go out in public, my body feels relaxed. I’m not bracing for someone to honk their horn at me when I’m trying to cross the street, or for the cashier at TJ Maxx to holler “NEXT!” in an impatient tone of voice. Everyone I smile at smiles back, and I don’t care if the smile is sincere. I know that people here sincerely want to be liked, which may have been why no one here voted for Donald Trump in the primary. Growing up, we learned that people who don’t care if they’re liked—who don’t show consideration of the feelings of others—don’t deserve to be.

The presumptive Republican candidate is a natural byproduct of an economy where individuals are expected to optimize their potential through their virtual self-presentation—reality-based fiction—in much the way Laura’s father, Pa Ingalls, optimized his wheat harvest with a machine thresher. In the age of social media, it may be time to update Wilder’s aphorism: Grown-up people must always leverage their feelings in order to promote their personal brands. In this context, Wilder-style restraint seems quaint, even childish.

When I was a kid reading Little House, I hoped one day to grow out of my feelings, to buckle on my emotional corset, handle adversity with grace, and never disappoint those I loved with my bad moods. Instead I turned into a writer. My work makes self-disclosure a daily question. I still wonder how to write about my feelings when I’m not sure if they are mine or Laura’s, if they are something to do with me or something to do with my upbringing, or the stories I loved as a child. I wonder if I am a grown-up, and if so, by whose standards. I wish I felt confident that I have the best words, but I’m glad I wonder whether they’re worth saying.